I came from a poor farming family in Takeo Province, and was educated with my older brother who was a monk. There were no schools in my area, so I studied at the temple. In 1959, I began studying at a regular school, but it was far from my home, so I rented a place in town. Once a week, I came home to get rice and other food to take back with me.

In 1962, I passed my baccalaureate I examination and a year later, applied to medical school. I applied to take examinations in many fields; I didn’t like medicine, but I passed it and jobs were difficult to find. After I passed, I was appointed to work for the Ministry of Public Health in Kampot province.

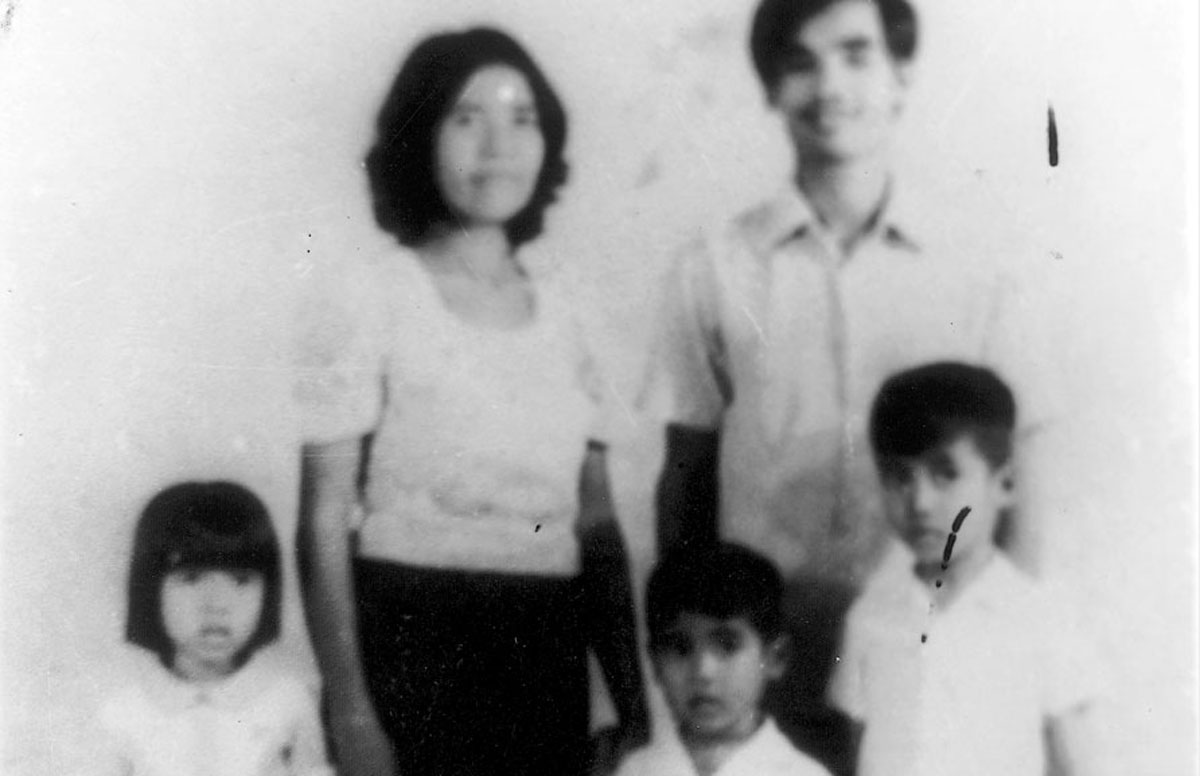

In 1965, I married Heng Savang. We spent two years in Kampot, then I was transferred to a hospital in Phnom Penh. There, I educated people about health problems and distributed food to children who were lacking vitamins.

Although I earned more money in the city than I could in the countryside, there was a lot of inflation in Cambodia during the 1970s, and the price of gold doubled. So, we did not have enough money to buy things. We lived with my mother in law in Kandal Province and I drove my car to work each day. I also earned extra money by visiting patients in their homes.

When the Khmer Rouge soldiers evacuated people out of the city, I did not bring my car along. We were in a hurry and packed only a few necessities, like clothes, rice, and dry food. When we arrived in Kampong Speu Province, the local people brought their ox carts to greet the city people. The Angkar had us stand in rows, asked us about our past, and took all the belongings we had brought from the city and gave them to the cooperative. Then they handed us black clothes to wear.

“What can you do?” the cadres asked me. I responded, “I can do all kind of labor.” I could polish wood for making looms because I done this with my parents in the countryside. The Angkar first asked me to make small mills for grinding rice and then placed me in a cooperative that made looms. Later, they suspected me and questioned me again about my biography. I told the Angkar I was a carpenter at a hospital. So, they then had me build waterwheels, looms, and plows.

My first child died from lack of food and medical care at the end of 1975. I knew how to cure his disease, but did not have enough medicine. He was sent to the hospital, but the Khmer Rouge nurses did not care for him well, and he died there.

We grew many vegetables around our house. When I was not at home, my wife stole one of our pumpkins to make soup for our children. The cadres saw her and took her and my children to a subdistrict office, where they accused her of stealing the cooperative’s food. I also made a mistake when I stole some potatoes to eat. I was cooking them when the militia arrived. One of them kicked me hard and then tied my hands behind my back. They imprisoned me in the subdistrict office, but released me a day later when one of our neighbors begged the Angkar to forgive me. My wife and children were also released.

In October 1975, the Angkar moved many people in our village to Pursat Province. We rode in cars that sped along the roads. Each time one of the drivers stepped on the brakes, people fell out and were killed. My father and brother Chhan had been evacuated to Pursat, so I met them there, and then went on to Battambang Province with them.

When we arrived, tractors were waiting for us. Our living conditions were better in Battambang because we could find our own vegetables to eat and the Angkar there was not as strict. I was ordered to chop down trees in the jungle. My cousin was with me as well. One day he didn’t go to work because he had malaria. The Angkar sent him to be killed.

At the end of 1978, the Angkar ordered me to work as a witch doctor and to cremate people’s corpses. I went to the jungle to find herbs to make medicines, and saw many dead bodies there. I cremated corpses three times a day, but sometimes I couldn’t find enough brush and had to bury them instead.

One day, the Angkar called me and my brother-in-law to bury 21 people. They had not been killed yet, and were in the jungle chopping down trees. When we arrived, I heard them whispering that soon there would be many Vietnamese soldiers coming to liberate us. Those 21 people had found a radio in the jungle and had listened to it. Moments later, the Angkar chopped their heads off, and my brother and I buried them in one shallow grave.