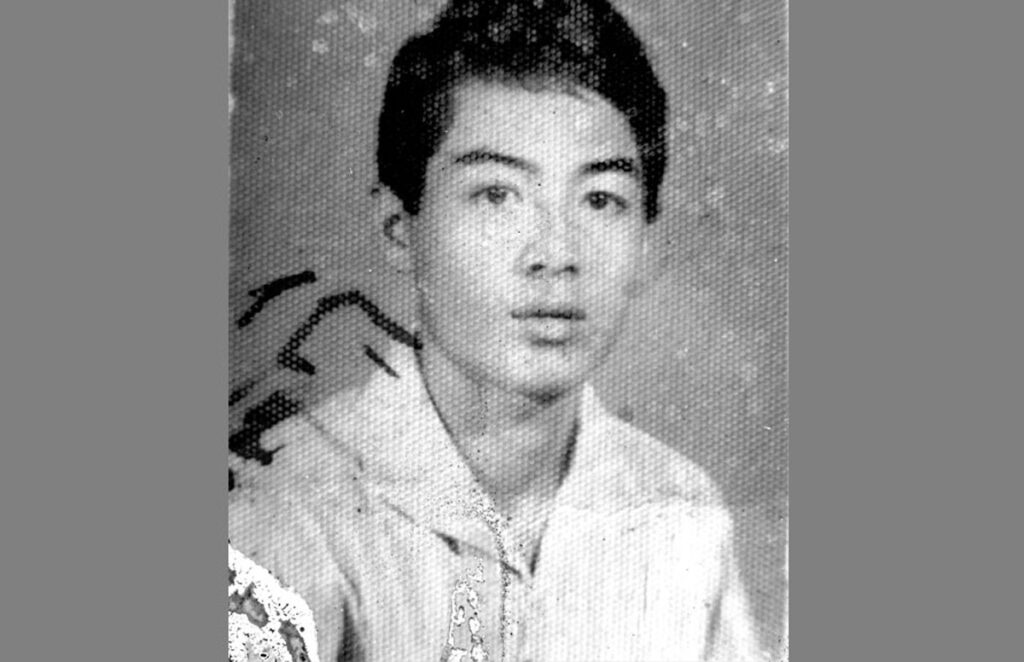

My father was the chief of forest and wild animal preservation at the Ministry of Agriculture. In 1973, the Ministry assigned him to monitor along the Koh Kong coastline. He decided to move his family to Koh Kong after the Khmer New Year of 1975, but everything changed on April 17.

When the Khmer Rouge seized Phnom Penh, our family was inside the Ministry. My father turned his office into a bomb shelter as the liberation army shelled the city. A senior commander from East Zone entered the Ministry’s compound. Because he didn’t know Phnom Penh, he asked my father to drive him around. I sat in the back of the Land Rover.

My father parked in front of a pharmacy and went inside with the commander. He came back with two sacks of medicine for malaria, diarrhea, and pain. “You told me you are a chauffeur. Why do you know many kinds of drugs?” the commander asked.

“It is not strange for the chauffeur of a forest warden to know many medicines. I usually drive to malarial regions, so I have learned to recognize and use drugs,” my father answered with smile.

“Angkar announced that the population will be evacuated just for a short period of time – three days. In fact, it is uncertain when will they will be allowed to return. When you move to the countryside, you should not bring money with you because money will not be used there. You’d better bring as much rice, salt and fish paste as possible. Since you are just a chauffeur, you will not have any problem. But military and government officials will be in trouble,” he told my father in a whisper. “My unit will head to Battambang. If you don’t mind, go with us…I will accompany your family to your hometown,” said the commander, knowing that my father was born in Pursat.

But when my parents discussed this, my mother refused to go to Pursat. She missed her relatives in the liberated region (they had been separated for several years), and my father did not refuse her wish. So all of us moved to her father’s village of Kporp Leu in Kandal Province.

A cooperative militiaman named Sat lived about 50 meters from our house. He had a black list, and the Angkar allowed him to make unlimited decisions to kill people. The black list contained the names of April 17 people and some base people who were Chinese or Kampuchea Kroam [Cambodians whose villages had been annexed by Vietnam]. Their lives were determined by Sat’s red pen. Anyone whose name was written in red ink would be killed.

My aunt Gnoeng sometimes begged Sat to spare my father. After she did this many times, he told Gnoeng, “Don’t worry… if I want him to die, he will…” Gnoeng believed that Sat said this without understanding the meaning of his words. That night, militiamen tied my father up and walked him away.

Of my five siblings, it was my oldest sister who saw our father for the last time. During the lunch break one day, people were being served watery rice soup. My father saw my sister looking for a spoon. “Where is your spoon?” he whispered to her. She replied, “I lost it last night. I didn’t know who took it…” “Take mine, and eat as quickly as you can,” he said, handing his spoon to my sister.

“What about you?” my sister asked. “That’s all right! You keep it for yourself,” answered my father. Then he headed back to the dining place hall for older people.

My father certainly understood that a plate and spoon were substantial personal belongings, and they were the only personal possessions allowed under the Angkar’s policy. Every individual had a small bag containing nothing but a spoon and a plate.

That evening, my sister stole a spoon from the communal dining hall, thinking she would return my father’s spoon to him. She looked for my father the next morning, but could not find him. She approached an older people’s group during the lunch break and asked about my father. Moeun, who was in my father’s canal digging group, rushed to my sister and asked: “Are you coming to see your father?” “Yes! I want to give him his spoon,” my sister replied. “There’s no need to find him. He has been sent to work far away,” replied Moeun with a sad face. My sister understood Moeun’s words.

Moeun told her later that militiamen came to the canal where he and my father were working. The generator operator turned off the engine and the worksite went dark. Then they tied my father up and walked him to the village by the river.

Yoeng, the cooperative chief, scornfully told Gnoeng the next day: “Last night, I escorted Meng to the boat, and his warm tears fell onto my hand… On the boat, Meng begged me to loosen his ties because they made it difficult for him to sit….”

Yoeng’s parents lived near our house. He and my mother had been friends when they were young and used to play together. But during the regime, he had become so powerful

that none of the villagers in Kporp Leu dared to look into his eyes. Ever since we arrived, he had used the excuse of paying a visit to his parents so he could observe my father.

Yoeng said that my father was tortured and killed that night by the security unit of Koh Thmey prison. Yoeng followed the Khmer Rouge slogan “To dig up grass, one must dig up the roots.” So, after my father was killed, he ordered me to build myself in a youth mobile work brigade in another village. By so doing, he expected me to be smashed.

My sister kept the spoon she stole for my father and still has it today. She placed it next to my father’s picture and worships it as one of our family’s most precious possessions.