I never went to school, but my husband Hai Sang was literate. He was half Chinese and came from Kampong Speu Province. He had relatives who lived next door to our house in Phnom Penh. They liked me, and asked my parents if I was available. They told Hai Sang about me, so he came around to take a secret look at me. His parents gave presents to our family, and we got married. I never saw him until our wedding day.

After we got married, my we lived with my husband’s family for a month. But my parents missed me terribly and were afraid his relatives weren’t treating me well enough, so they asked us to live with them. I didn’t have any problem with my in-laws, but we moved to my parents’ house anyway.

My father suggested that Hai Sang take a course at the Wat Phnom Driving School. It cost 500 riel to learn how to drive. My husband then became a truck driver. He transported bricks, iron, steel, sand, and cement. He could earn around 1000 to 2000 riel per month, which was enough support the whole family. I stayed home to look after the children.

On April 17, 1975 the Khmer Rouge claimed that people must leave Phnom Penh as soon as possible. They added we could return to the city after three days, and we totally believed what they told us. We took only a little food and a few belongings. My eleven children had to carry food, clothes, and water.

It was difficult for me to travel because it was nearing time for me to give birth. Along the way, the Angkar wanted to kill us, but I begged them saying that I was about to have a baby and had many children to care for. Not long after we reached Kampong Chhnang Province, I gave birth to a son.

When the Khmer Rouge asked about our biographies, I told them Hai Sang was a truck driver and I was a vegetable seller. Some people believed me, but others did not believe me at all. My husband was ordered to drive fish to the market and young people to the rice fields. He came home only once or twice a month.

We didn’t have much to eat at all, only 2 grams of rice for each meal. It wasn’t enough to feed my children, so I had to cook it into rice soup. We didn’t even have salt. Once I saw some villagers steal a little of the Angkar’s food. When the Angkar found out, they were sent deep in the jungle to be killed.

Only two of my children were allowed to live with me; the others were in mobile brigades. Some of the base people’s children fought with mine. When they hit my children, I became very angry and hit some of the base people’s children. Then my unit chief scolded me terribly.

Some of the local people insulted me, saying, “Those who used to live so comfortably with luxuries like cars and motorbikes do not know how to work, but only know how to eat.’ Others were jealous because I had many children and got more portions of rice, which were based on the number of people in a family.

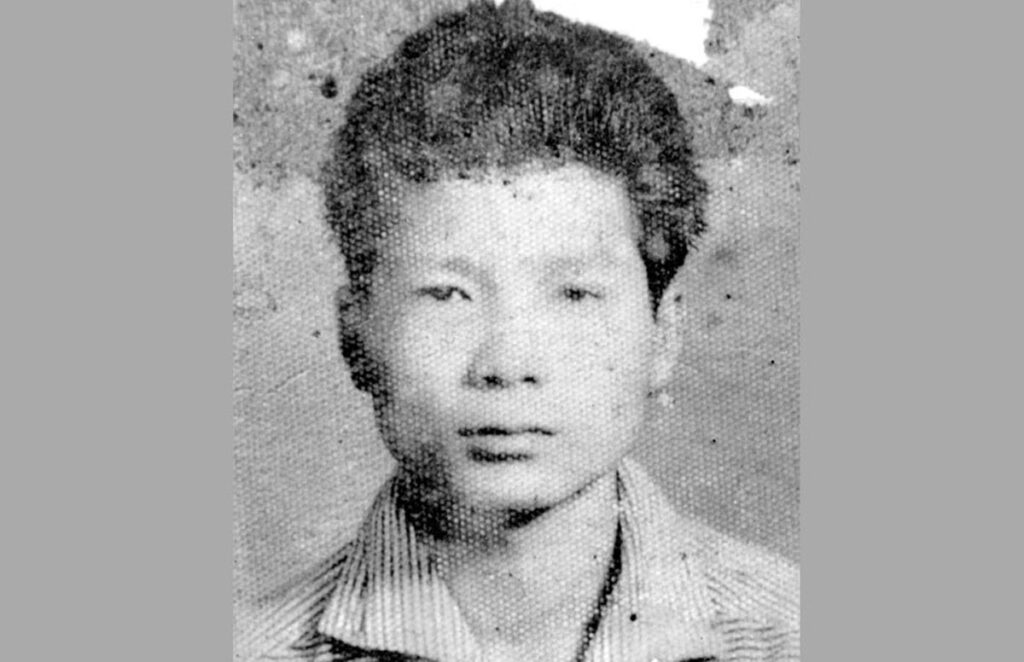

When I look at my husband’s photo, it reminds me of how hard he worked to support us and that our family lived comfortably. Hai Sang is dead now and is at peace.