Bun Lorn worked near Rorka Kong market in Kandal Province. I used to go there to buy food for my family. He watched me for a year, but I didn’t really notice him. One day, his parents came to mine and arranged our marriage. I didn’t meet him until our wedding day in 1969. I was 19 when we were married.

After our wedding, I went to live with his parents. My parents were old fashioned; they preferred that their daughters stay at home to do chores, so I didn’t have the opportunity to be educated.

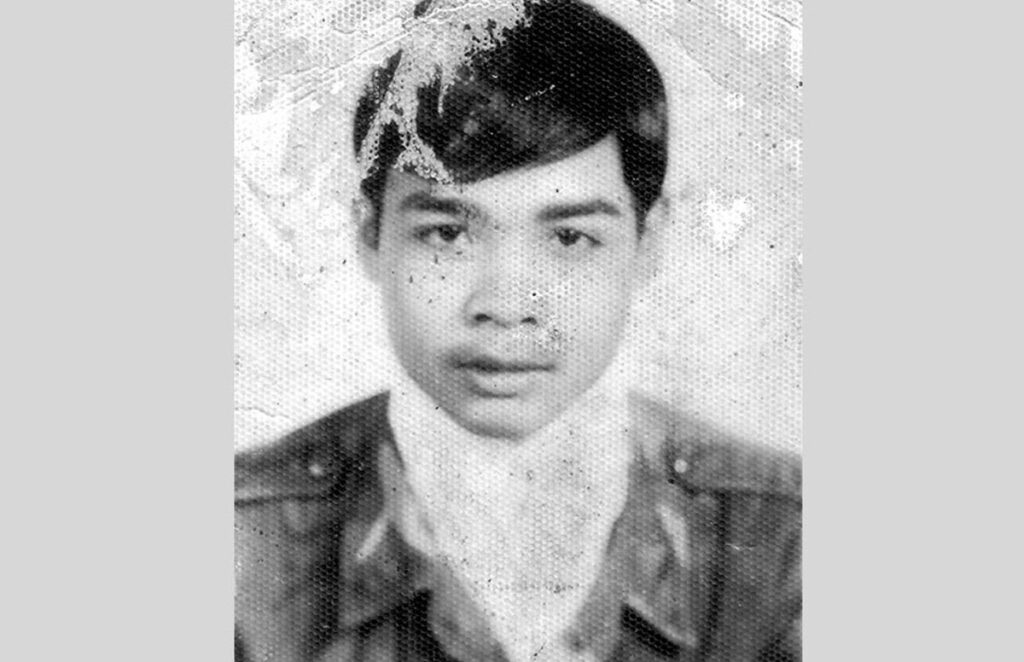

Bun Lorn was born in Phnom Penh; his father was a construction engineer. When he was 14, his parents moved to a district near ours in Kandal. After the 1970 coup d’etat, he joined the army. Bun Lorn was transferred to Udong when we had been married for six months, but resigned to help his parents weave scarves. In 1973, there were many bombings in our village and both his family and mine moved to Phnom Penh.

We decided to return to Bun Lorn’s village when the Khmer Rouge evacuated the city. But when we got there, we saw that the house had been pulled down; only the roof remained. So, we cut some coconut palm leaves to make walls. After a while, my husband and I decided to move back to my hometown.

In late 1976, the Angkar transferred us and other people who had lived in Phnom Penh before the regime to Por Village in Pursat Province. There was no one living where they sent us, but they were planning to make a cooperative there. Por was a remote area; it didn’t have any plantations, but the land was good and we soon began growing rice. I planted rice and pulled out seedlings, while my husband worked in the plowing unit. Even though we grew plenty of rice, we did not have enough to eat. I became thinner and thinner, and when my first child was four months old, he died because I didn’t produce enough milk for him.

Bun Lorn soon became seriously ill with malaria and died. I didn’t even have a chance to take him to the hospital. I too, was sick and could barely walk, so other villagers took his corpse away. I don’t know where he is buried.

After that, I lived every day in fear. Bun Lorn had solved all the difficult problems we had encountered, but then he was gone. At first, Por village had 300 families, but after a year or so, there were only 17 left; they disappeared one after the other. I stayed until the Vietnamese soldiers came in 1979 and told us to return home. I walked for a month before I was able to get back to my village.