I married two men; both were my relatives. My first marriage was arranged to a farmer from my village in Phnom Penh. After we were married, he helped sell cakes at a shop near O Russey market and I farmed. Although he earned 1,300 riel a month, he never gave me any money. After we had been married for nine months, I decided to get a divorce. We never did get along well.

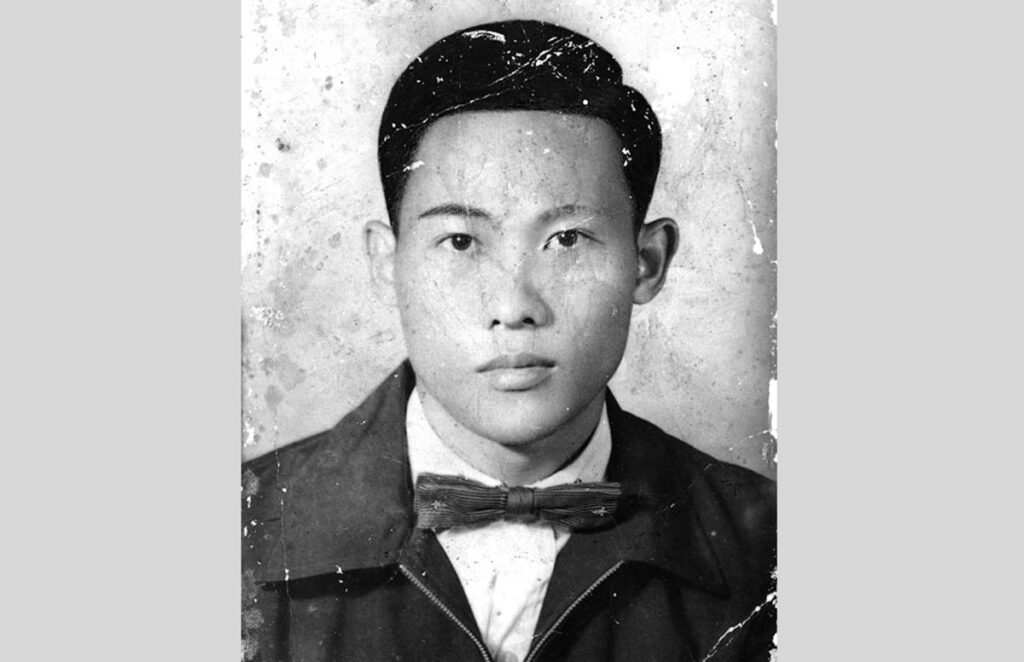

The second time was different; I was entitled to decide who I would marry. So the following year, I married Mak Tun. He had studied at Kak Khsach Pagoda and been ordained as a monk. He was a kind, handsome man, but poorly educated.

I was also poorly educated because my family was poor. When I was 15, I took a class for the illiterate. I studied for a year and was the best among the twenty students.

After my second marriage, I made cakes of palm and fermented rice and sold them in Phnom Penh. Mak Tun was a cyclo [pedicab] driver. He had dinner at home sometimes, but usually he came home only once a week.

During the Lon Nol regime, the Khmer Rouge took over my village and it was constantly bombarded, so my family and other villagers moved a little out of the city to Chamkar Daung. My husband built a cottage; it was just big enough for a bed, and we lived there for three years. He helped me sell palm juice and farm. We had a child.

When the Khmer Rouge drove people out of Phnom Penh, my second child was just a month old. It was very difficult for me to walk and carry my child at the same time because I had night blindness. My husband put our things on a cow cart and headed for Kandal Province, but the Khmer Rouge militiamen told us to go to Siem Reap instead. When we arrived there, my husband began building us a place to stay. Four or five months later, he managed to roof the cottage with palm leaves. It took us a year to have a proper house.

My husband worked in a plowing unit and my job was to cook porridge for pigs and pull out seedlings. Sometimes, I transplanted rice seedlings night and day. I was never idle or careless in my work because I feared death. Those who were lazy were taken away in the night and killed. A woman who lived near our cottage complained about the food shortage and asked where the rice went. The Angkar arrested her and her husband. They took them away and put their children in children’s units.

On 10th, 20th and 30th of the month, the Angkar would call people to a day-long meeting about equality in work and increasing farm production. I doubted that all the rice produced was being kept in the granary because people were starving.

In our village, the new people were not entitled to talk. Even when I walked to work and saw my husband along the street, I wasn’t allowed to look at his face. And when I was sick and in the hospital, the Angkar did not permit my husband to take care of me. All they gave me was medicine made from tree roots; it looked like rabbit dung.

In 1977, Choeun, the chief of the farming unit, asked my husband if they could exchange cows. Mak Tun did not agree to do this because we had brought that cow with us from Phnom Penh. Then the Angkar accused him of being a colonel. A month later, they called him and about 80 other men to clear forests. At about 7 in the morning, two militiamen took them out of the village. The village chief told me not to worry because he would come back in 9 months and 10 days.

The villagers whispered to me that 9 months and 10 days meant my husband was killed and reincarnated. A woman whose husband was also called by Angkar told me that she saw a militiaman bring my husband to Sa-ang Prison, and that those sent to Sa-ang rarely survived. I have not received any information about him since.

I feel much regret that I wasn’t able to meet my husband for one last time.