I moved to Phnom Penh from Kandal Province so I could attend high school, but after I completed the 5th grade [the equivalent of 7th grade in the west] I took an entrance exam for the postal service. I passed and began working at the post office in 1961.

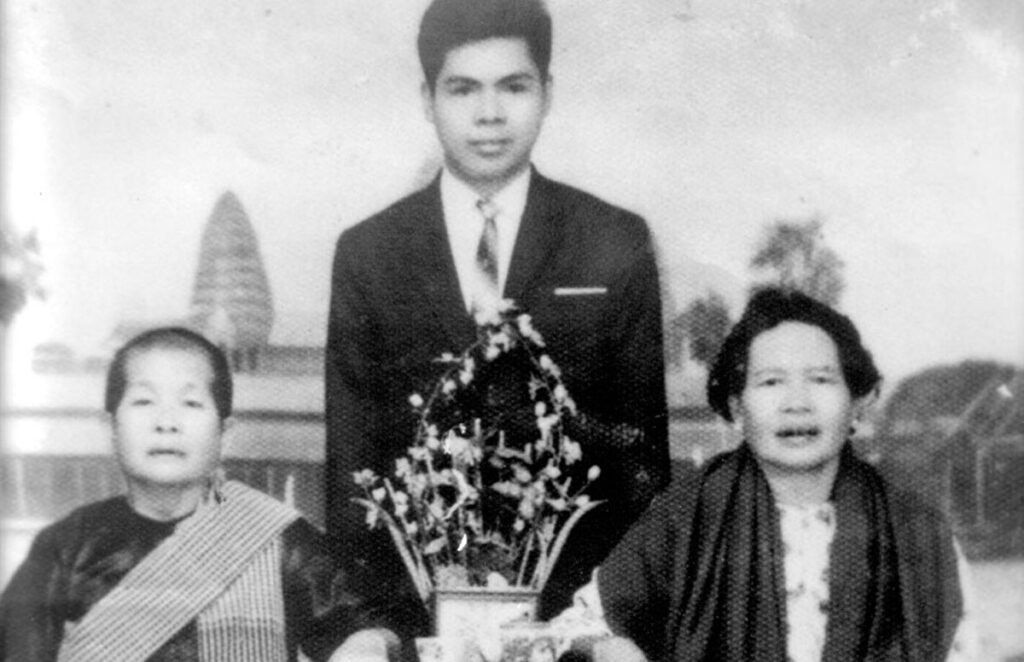

I fell in love with Say Ngim when she cut my hair and gave me a head massage at a hairdressing shop she rented along Kampuchea Krom Street. We married in 1963 and had four children. We had a middle-class family and were happy. However, our happiness did not last once the Khmer Rouge took control of Phnom Penh in 1975.

We were told to evacuate the city for only three days because the Americans would be dropping bombs. We put some of our belongings on our motorbike and carried things as well. It took us 15 days to reach my home village.

Soon after we arrived, I was asked about my biography. Everyone in the village knew that I had been working in Phnom Penh, so it was impossible for me to lie.

Living became a nightmare; I was afraid that one day I would be captured like the many government officials who were taken away from the village. One of my friends who had been a soldier was sent to be killed the day after he arrived.

Half of the people in the village were new people. While I was designated as one of the new people, my relatives in the village were base people. They controlled us and assigned us work. I dug canals and my wife became a farmer. The work was hard; one day, I had to dig a 5 meter square canal, and we had little to eat.

Luckily, I met the chief of Koh Thom Region; he had been my math teacher. Once I addressed him as “Teacher,” but he told me to call him “Comrade” instead. He told me to always obey the Angkar’s rules. I told him frankly that people in the village were being killed, and that I was afraid I would be killed one day. So, he wrote an official letter and gave it to his deputy so that I would be transferred to Battambang Province at the end of 1976. The letter assigned me to travel in the third train line. I discovered that all of the people who were in the first and second train lines were killed.

In Battambang, the Angkar asked about our biographies again. I told them that I was a barber. Even though I knew nothing about cutting hair, I was given that job. My wife also worked as a barber, while three of our children were sent to work in a children’s unit.

Our seven month-old son lived with my wife.

When I was first given scissors, I was afraid if I gave a soldier a bad haircut, I would be in big trouble. However, I had to do it. Without realizing it, I became an expert barber. Since many people got in line for haircuts, my legs became swollen from standing for many hours at a time. The chief of the region felt sorry for me and told me to rest in a hammock and put my legs up. However, it didn’t help because my legs had swollen from malnutrition. The medics gave me a lot of palm juice to drink, and I got a serious diarrhea. Within three days, my legs were no longer swollen because I became just like a skeleton.

In December 1978, the Khmer Rouge let us eat whatever we felt like. I didn’t eat a lot because my stomach had become used to eating very little and my younger brother almost died from overeating. When I began gaining a little weight, the region chief said, “I want you to die, but you are still alive.” I said it might not yet be time for me to die.

At the end of 1978 or early 1979, my wife was made chief of a rice mill. She reported to the sub-district chief that some of the base people were coming to steal rice from the mill. However, the chief was an old friend of one of the thieves, so he sent my wife and seven month-old son Sambo Chaul Krong to be killed.

I asked a unit chief who I knew about my wife and son. He used to be a water carrier for a Chinese family before the Khmer Rouge period. He could not even read or write, but now he had a high position in the regime. He told me that she was hit from the back and pushed into a grave, while my son was smashed against a coconut tree. I cried out loud when I learned this. I had become a widower with three children to look after.

After my wife’s death, the Angkar wanted me to marry a Khmer Rouge cadre. I refused, although it was risky. I was afraid that she would kill my children. A few days later, the regime collapsed.

Today, I have a good business working as a barber in Siem Reap. I went there because I wanted to see Angkor Wat before I died. My second wife is Put Mary. Her husband, a high-ranking Lon Nol soldier, was killed and her two children died during the Khmer Rouge regime. We started a family and had five children. I live at peace now.