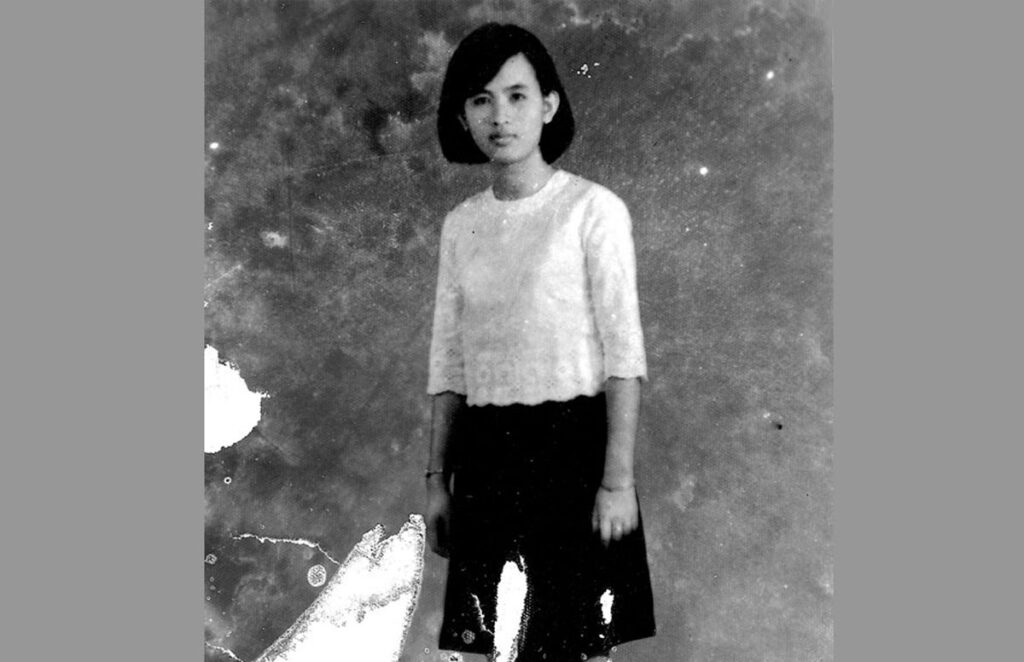

I was very lucky to marry my husband. If I had married a selfish man, I probably would have died from starvation during the Khmer Rouge regime. He was a handsome man and many girls were attracted to him.

We had gone to school together for four years before we got married. He always waited by the school gate for me, and sometimes left a letter or flower on my desk. My parents didn’t like my husband much. Once, my father sent me to live with my elderly uncle in Kampong Cham Province in the hopes that I would forget about him, but I stopped eating and drinking until I fell very ill. Then my father allowed me to return to Phnom Penh and agreed to let me marry.

After we married, I went to work at an office in Preh Monyvong Hospital in Phnom Penh. Although I learned some military tactics, I never went to the battlefield. My husband failed his secondary school examination, so he decided to work for his father, who owned a car garage.

My family members were evacuated separately on April 17. We met up near Kien Svay and waited there for the announcement that city dwellers could return to Phnom Penh. But then my parents and siblings went to live in Battambang Province, while my husband, our children, and I went to Banteay Meanchey.

The Angkar once told us that people who were Vietnamese could return to their country. So, I asked an elderly woman who was Vietnamese and could not speak Khmer clearly to be my mother. My husband and I changed our names to Vietnamese names. He became Kvang Huot and I was Kim Lang. Later, 20 Vietnamese families were taken out of the village. I heard they were put on boats; once the boats reached the middle of the river, the Angkar sank them. They played loud music to make it seem that nothing had happened. After that, we went back to our original names.

When I was hungry, my husband was the only one who tried to find food for me. I remember telling him that I wanted to have coffee. Without saying a word, he walked outside. A while later, he returned home wearing a grin. He made a fire and fried two handfuls of crispy rice until they were burned, and added a spoonful of palm sugar. Then he washed about five bulbs of kravanh root, pounded them, and added them to boiling water. After pouring the mixture into a coconut shell, he gave me my “coffee.”

Once when I was in labor, my husband ran out into the night to find the Khmer Rouge midwife. But she was busy; the village chief’s wife was delivering a baby at the same time. Besides, she didn’t want to come because my husband hadn’t given her a bribe. Nevertheless, I delivered a healthy baby boy with the help of my neighbor. The next morning, my husband cooked chicken porridge for the woman who helped me.

Before my husband went to work, he always told me not to wash the baby’s nappies, saying he would to it when he came back. But I ignored him and washed the nappies in an irrigation canal. I got beriberi on my legs from spending too much time in the water. My husband massaged my legs for a whole week. He then carried me to the hospital on his back, along with our baby son. It was 5 kilometers away and took forever.

I dreamed about a knife that was broken in half one night when the moon was full. It seemed that something bad was about to happen and I couldn’t go back to sleep. The next morning a cadre told my husband to plough a rice field. I handed him a cigarette lighter in case he needed it, then I went to work. While I was transplanting rice, a Khmer Rouge cadre mocked me, saying “Comrade, you have become a widow at a very young age. I really pity you.” “You must be mistaken Comrade, My husband is still alive,” I replied. I saw that same cadre later; he was using my husband’s cigarette lighter. I realized then that my husband would never come home.

Three of my children also died curing the regime. My first son Pheak died in 1978 from starvation. My second daughter Srass died from an illness in 1975. My third son died when he was three months old; he had an abscess near his kidney. If my husband had lived, he would have found enough food for them and they would not have died.

In 1979, I met a friend and told her that I was still waiting for my husband. She said I must have stepped on his head each time I walked across the rice field on my way to work. She was trying to tell me that my husband had died and was probably buried along the road I often took during the regime.

This story is based on an essay Heng Sokphanna wrote entitled “The Shadow of My Husband.” It was the first prize winter in a contest sponsored by the Khmer Writers Association and the Documentation Center of Cambodia in 2004.