When I was young I did not a chance to get an education. Although my siblings went to school, I stayed at home and worked as a farmer to support my family. I also took care of my sick parents.

My husband Chem Hing came from Kandal Province. One day, he went to visit his aunt in my home village and she persuaded him to ask for my hand in marriage. We became engaged and decided to get married a year later.

At first, my husband worked as a palm juice tapper and then decided to become a driver. He had to rent a car, which cost around 500 riel a month. He drove to places like Takhmau, but I never traveled with him on his long-distance trips. Even though he usually went to work early in the morning and returned late at night, he continued to tap palm trees, fish and farm.

Hing was the oldest son in his family, and had to support his nine younger siblings. We often faced financial problems because he had so many dependants. He was not an aggressive man and never argued with me or his family.

During the Lon Nol regime, a lot of bombs were dropped on our village, so many families decided to move temporarily to a town near Phnom Penh. When the bombs were being dropped during the harvest season, many of us would sneak back to the village to collect rice. Villagers also tried to get the rice that was being dropped from airplanes. This wasn’t easy because they dropped it far from the village near Pochetong Airport; the people who lived nearby got most of it. Later on, when the situation became a bit more stable, we would return to our village to dig crabs and gather firewood.

In April 1975, the Khmer Rouge soldiers started to force us to move out. I didn’t really know who they were, but we were afraid of them so we followed their orders. Eating our rice along the way, we started out for Kandal Province. When we arrived, we didn’t have any shelter, so we wove palm leaves together and made a thatched hut. Because we were new people, we were not allowed to live with the base people.

I worked at a rice mill and my husband sawed logs and chopped down palm trees. We had only sour water lily or banana soup to eat, even though we husked rice all day long. I don’t know what the base people ate, although they had the right to eat yellow corn. The Khmer Rouge cadres did have rice, though.

I think my husband’s relatives took him to be killed. His uncle was a Khmer Rouge soldier as well as a base person. One night, his uncle came to our house and told Hing not cut trees the next day, but go instead to Bati River. My husband had a gut feeling about this. He said, “Uncle, I know you are taking me away to be killed, so you don’t have to tell me this.” His parents had a dream that if my husband was sent away during the morning or at night, he would be killed, but if he was sent away in the afternoon, he would be safe. Hing’s uncle asked him to go at night, but my husband said no, he would go in the morning.

Hing said to his uncle, “You are taking me away. You don’t have to lie to me, telling me you are sending me to work.” At eight o’clock the next the morning, my husband was tied with a rope along with other two villagers. No one in the village dared to glance at him. I didn’t learn about this until two days later because I was out husking rice.

I think he was killed at Sa-ang prison. A woman named Trap, who was from my husband’s hometown, was imprisoned there. After 1979, she told me that she wanted to escape from Sa-ang and asked Hing to come along. My husband said no; both this hands and legs were shackled. He knew he would be killed either way: in the prison or trying to escape.

After Hing disappeared, the Angkar took me for re-education. They ordered me to dig a hole in the ground and bury myself in it because I wasn’t husking rice fast enough. I asked them what I had done wrong and they screamed back that I had dared to defy the Angkar. I told them I hadn’t done anything so bad that the Angkar should bury me. I also said that they had taken away my husband; why should I be punished again?

Two of my children were killed when the Angkar ordered people to dig trenches around a temple. Suddenly, a bomb exploded and my children died instantly. It was like what my husband said: you could die either way, at the construction site or by defying the Angkar’s orders.

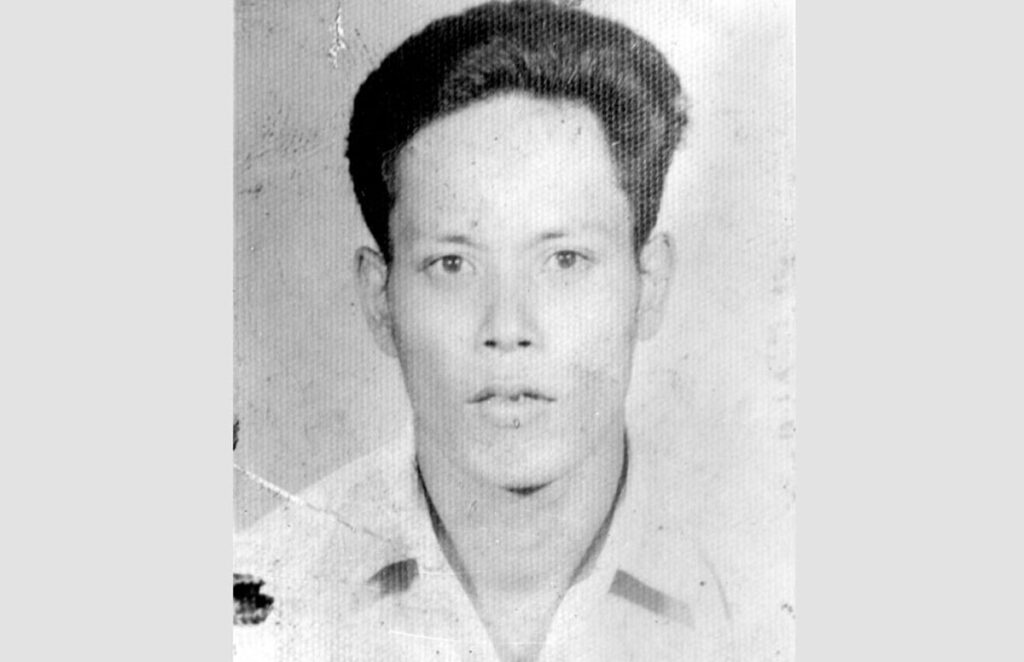

My mother in law hid this photo in an areca nut box during the regime. I show it to my children so they can remember their father’s face.

My children used to visit a fortune teller who told them that Hing was still alive and would return home in December. I looked for him every December since 1979. I also hired a medium who trampled on my husband’s photograph so that I could see him face to face. But I could only see him sitting while he was shackled. Now, when I look at his photo, I see it is losing its color. I no longer have feelings about it and know he is dead.