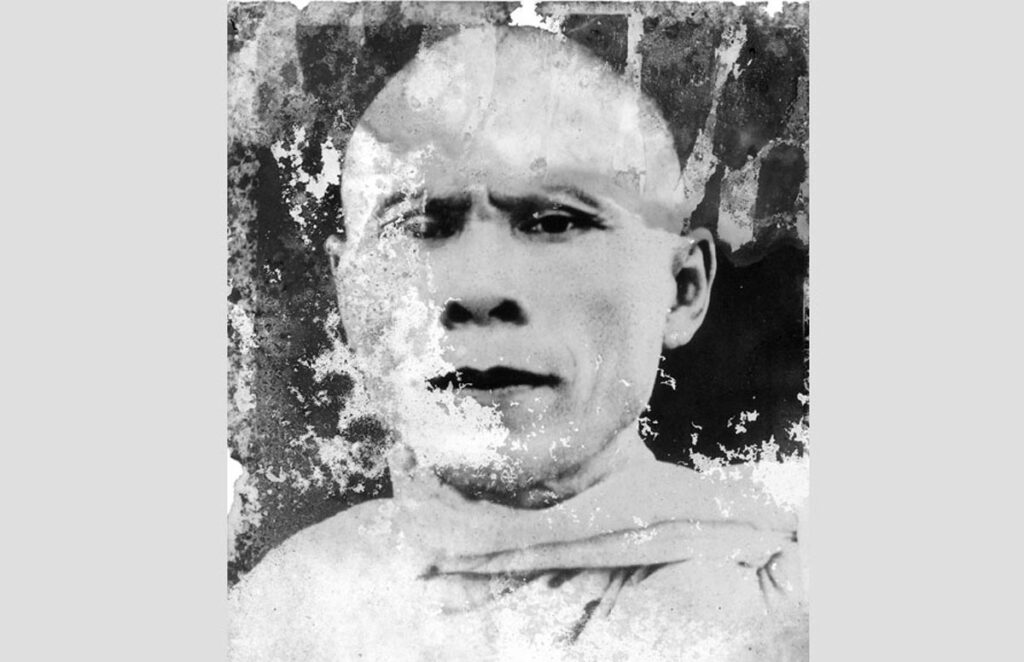

Chaing Chaem was head of the Tet Mountain Buddhist monastery in Chamkar Leu District of Kampong Cham Province. He was very famous for his black magic, and many people still remember him. My grandmother Voek was a Buddhist nun who also respected and believed in his magical powers.

When I was young, she took me to pay respect to Chaing Chaem; she also wanted to ask him to change my original name, which was Neou Kim Sieng. As we approached him but before my grandmother had a chance to speak, Chaing Chaem shouted, “Call him Kim Ann, and he will no longer get sick.”

Another time, I witnessed a miracle he performed. He came out of the dining hall and called to the nuns in the rice fields, “Come up, please.” I looked to the place where he was pointing and saw many nuns walking in the fields. But when I looked again a moment later, there was no one. This made me believe in his magical powers.

A year after the 1970 coup d’état, Chaing Chaem fled from the monastery. I don’t know why, but I do know he had a kinship with the royal family and was a supporter of the King. After the Khmer Rouge’s victory, I saw him returning to Bos Khnaor village; he was wearing a yellow robe. Several days later, the village chief sent him to a security office about a kilometer from my house. The villagers were very happy about his return and came to see him, but the Khmer Rouge would not allow anyone to bring him food. After two weeks, the Khmer Rouge undermined his powers by removing his magical hip laces and then killed him at 6:30 in the evening. Some villagers did not believe he was killed, and in 1986-1987 I heard them say there was a monk who looked very much like Chaing Chaem. They concluded he hadn’t died, but had been ordained again.

My father Neou Try had been a volunteer soldier during King Sihanouk’s reign. In 1970, while he was leading a group of demonstrators against the coup d’etat, Lon Nol soldiers shot off one of his ears. They chased him after that, so he fled and hid in the forest, and then served in the liberation army for a short time. I used to bring him medicine and rice in the jungle. When the situation calmed down, he returned to our village in Kampong Cham Province.

The Khmer Rouge evacuated our family three times before they took power over Cambodia. The first time was in 1971, when they made us move about 40 kilometers east of our village. When we returned, our house had been burned down. We were evacuated again in 1972 and two years later we returned to our village. In 1975 we were evacuated to Chamkar Leu District and lived there until 1979.

My father’s mother Voek lived with us during the regime. She had been a Buddhist nun after the death of her husband; my father was just four years old when he died. The Khmer Rouge assigned her to look after small children, weave mats, and polish. She died of starvation. Her sister Chiro was also a widow. She had sent my father a letter asking him to bring her to his village, but my father was afraid because my family was targeted by the Khmer Rouge. Later I learned that Chiro and her daughter It were evacuated to Kampong Cham and died there.

In the dry season of 1977 we had almost no rain, causing many cows die. The Angkar allowed villagers to take them to eat. My sister did not eat beef, so I cut a fruitless papaya tree to make chhai peou [a salty preserve] for her. The Angkar accused me of destroying its papaya tree. Pan, the chief of my unit, tricked me, saying I should go to the office of Samaki Village, where I was to collect food and bring it to our work site. When I arrived, the village chief slapped me on the face and pulled my hair. Then he ordered Chan, a militiaman, to tie my hands behind my back and bring me to the bamboo forest east of the village. Chan hit me hard, but I didn’t feel it because I was too afraid. The bamboo forest behind the village’s security office was a killing field.

“Brother Comrade,” I cried, “I cut the papaya tree because it has not borne fruit for two years and it will not bear again. If you don’t believe me, please go and see it.” The chief whispered something to the militiaman, who then loosened my bonds a little and chained me up in the security office. The guard questioned me quite reasonably, and then removed my shackles. I was given the job of collecting 12 buckets of manure a day. I worked hard in order to gain the Angkar’s trust. After a month, I was sent back to my old sub-district.

One night while I was threshing rice, I saw a Land Rover come out of the rubber plantation and drive to a village that was about 700 meters from where I was standing. After lunch the next day, I followed the Land Rover’s tracks. As I was walking, I felt that something was under my shoes, so I bent down and saw coagulating blood on the dead leaves. I followed the blood to a deep well and looked inside. It held many corpses. From then on, I was terribly scared and tried to build myself with hard work.

Seeing I was a clever child, the Angkar wanted to place me in a special unit of a ministry. However, they said my name was Vietnamese and would not let me join. So they sent me to agricultural training at Stung Kdei Dam, where I stayed until the Vietnamese army storm attacked Cambodia at the end of 1978.

Neou Kim Ann submitted this story to a 2004 essay contest on Khmer Rouge history sponsored by the Khmer Writers Association and the Documentation Center of Cambodia.