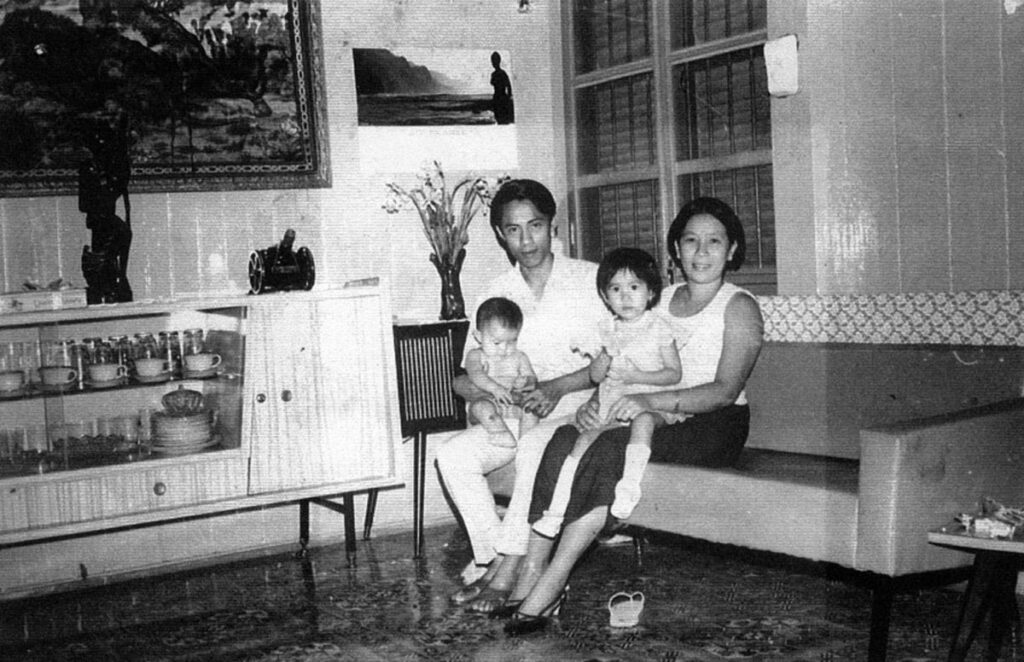

Told by his daughter, Buth Chan Mearadey

My father, who was born in 1920, was a real patriot and very active in politics. He was a representative in the National Assembly for two terms, from 1959 to 1967, and was involved in the coup to depose King Sihanouk in 1970. He had a lot of friends in the Khmer Republic government. Two of them were Lon Nol [prime minister] and Sirik Matak [the prince who the French passed over for the throne in favor of his cousin Norodom Sihanouk and became deputy prime minister]. During the Lon Nol regime, he worked first in the Ministry of Planning and then in Phnom Penh City Hall.

Even though my father had a lot of information from his political connections, he always believed that Cambodia was a good, safe country, so he didn’t want to run away when the Khmer Rouge took over.

In April 1975, our family was living in a big house in Phnom Penh. There were fourteen of us: my parents; my husband and I and our two children; my sister Rasmei, her husband and two children; my sisters Sousdey and Thida; and two maids. My father wanted all of his family to live together.

On the third day after the Khmer Rouge entered Phnom Penh and started shooting, we left the city in two small cars. There were so many people on the road that we weren’t able to drive, so we had to push them. Along the way, we saw many dead bodies; there was so much fighting that they didn’t take the corpses away.

First they evacuated our family to Chbar Ampouv and Kbal Thnal; then we went to Chroy Ampil and left the cars there. My brother-in-law heard people talking about my father in Chroy Ampil. They pointed to him, saying, “He is Buth Choun.” We didn’t know who they were, but they knew us. We didn’t pay much attention because we didn’t think there would be any problems for us.

We went to the boat dock at Prek Por. At midnight, three or four young men dressed in black came to the dock. The said they had come to take my father to meet the Angkar and get some information from him. My father was not concerned and decided to go with them.

We waited a long time for him. At around 2 in the morning, the Angkar brought a letter, saying it was from my father. He wrote that he would be arrested in a short while and that we should not wait for him. He also said if he were lucky, he would meet us in Chamkar Leu. I remember everything in the letter, even though I lost it many years later.

The next day, we continued to Chamkar Leu by boat, and on from there to my mother’s hometown of Speu Village in in Kampong Cham Province. We prayed our relatives there would help us. The villagers told us we shouldn’t continue thinking my father was still alive because the Khmer Rouge didn’t keep people who were high ranking. I kept up hope, but after a year, when many people were killed, I began to feel the disappointment of losing him. We never heard anything about him after that.

Chamkar Leu was a good district. There 16 families of old people and 2 families of new people in our village. The land was good and there was enough food. I stole food sometimes, but was never caught. The villagers, who were good people, taught me to transplant rice and pick beans from the villagers, and I became strong.

They started sending people to be killed in July or August of 1977. Before that, they only took those they knew were soldiers or people with high rank. But in 1977, they began taking teachers, too.

One of my neighbors was the widow of a Lon Nol soldier. One night, the Khmer Rouge came to call her family, but they escaped. She knew that the Angkar would take them to be killed, so she called her four daughters from their workplaces. The next morning, they found them dead; they had cut their own throats under a mango tree.

The villagers had a homemade radio that they kept hidden underground and we sometimes listened to Voice of America on it at night. In January 1979, we heard they were evacuating people to Thailand, so we all decided to leave the village. Nearly 30 of us left together.

We walked for about a month, sometimes up to 20 km a day. When we reached Siem Reap, my sister Rasmei gave birth, so we stayed there about a month. Then we found a guide who took us through the jungle to Thailand. He tried to abandon us in the forest. But the villagers climbed up trees, and when they didn’t see any lights, knew we hadn’t arrived and forced him to take us all the way.

When the Americans at the refugee camp learned about my husband’s background, they registered us so we could emigrate to a third country. Eventually, all of us made it out. My husband, our three children and I went to the United States and later brought my mother to live with us. My sisters Thida and Sousdey also came with their children, and my sister Rasmei and her family went to Canada. Today I am a social worker in California.

One day, they tied my husband Ngak Kheang up with a rope and took him to the security office about an hour’s walk from our village. A week after they arrested him, I saw Hok, the region chief, riding a motorbike past our house. I flagged him down and asked him why the Angkar had arrested my husband. I said Kheang wasn’t a soldier or a businessman; he had only been a teacher.

My husband had been a teacher in Speu Village from 1966 until 1968, but then moved to Phnom Penh to teach grade 4 or 5; he taught French as well. One of the village chief’s children had been his pupil, so they knew about him. His students liked him and when we were first evacuated to Chamkar Leu, they made sure we had enough food.

Around 1970, my husband quit teaching and went to work at the French newspaper AKP. People in the National Assembly read it. Kheang was a translator and also wrote articles; some of them appeared on the front page. Sometimes people criticized him for writing about what was happening locally, particularly his articles on politics and the National Assembly.

Hok said he would ask my husband about his past; then he left. Hok did go to see my Kheang, and told him that he had been a teacher as well. They agreed on many ideas and Hok told my husband that he should leave Speu Village because it was no longer safe; a lot of the old people in the village didn’t like us. Then Hok devised a plan to get my husband out of prison and he was released to a farm nearby. Hok was a good man; later, he disappeared.

They tried to arrest Kheang again, but he evaded the Khmer Rouge. When he came home, the village chief was surprised; he thought my husband had already been arrested.

After that, the Khmer Rouge wanted to send my mother and sister Thida to Region 42. I asked On, a soldier from the Southwest Zone, for permission to go with them. But they said my husband could not go. So, I went to the village chief and told him I needed to live with both my mother and my husband.

Both On and Hok wanted to help us, so they said that when the car came to take us away, we should not get in, but instead go back home and tell the Angkar that the car had left without us. We followed their instructions and four or five days later, saw the clothing of the people who had left in the car. They had been taken to a rubber plantation and thrown in a well. The Khmer Rouge gave other people their clothes and sold their watches. My uncle and his family were among those killed.

Buth Chan Meaready’s sisters remember their father:

In our culture, people were always afraid of their fathers, but our father made us comfortable when we were around him. He was a big entertainer, and told us that he was once the lead character in the famous play Sophat. He played drums in a band with his friends, and the organ almost every night. In 1960, he took us to a live concert where Mr. Chum Kem performed “The Twist.” – Rasmei

My father was a kind and gentle person who encouraged us to study. He not only looked after his family, but his two sisters too. He gave their sons a home and food when they wanted to study in the city. He kindness didn’t stop there; sometimes he also helped those who came from his hometown. – Sousdey

I was only 15 when the Khmer Rouge abducted my father from my family. It was very early morning, so I was disoriented. We were on the Khmer Rouge ferry when my father walked to me, gently touched my head and told me “don’t go anywhere child, wait here…” He smiled gently at me to assure me that everything was going to be all right. I felt loved and protected. That was the last image of my father that remains with me to this day. For some reason, I remember that moment extremely well; it was surreal. I have longed for that love and protection ever since. – Thida