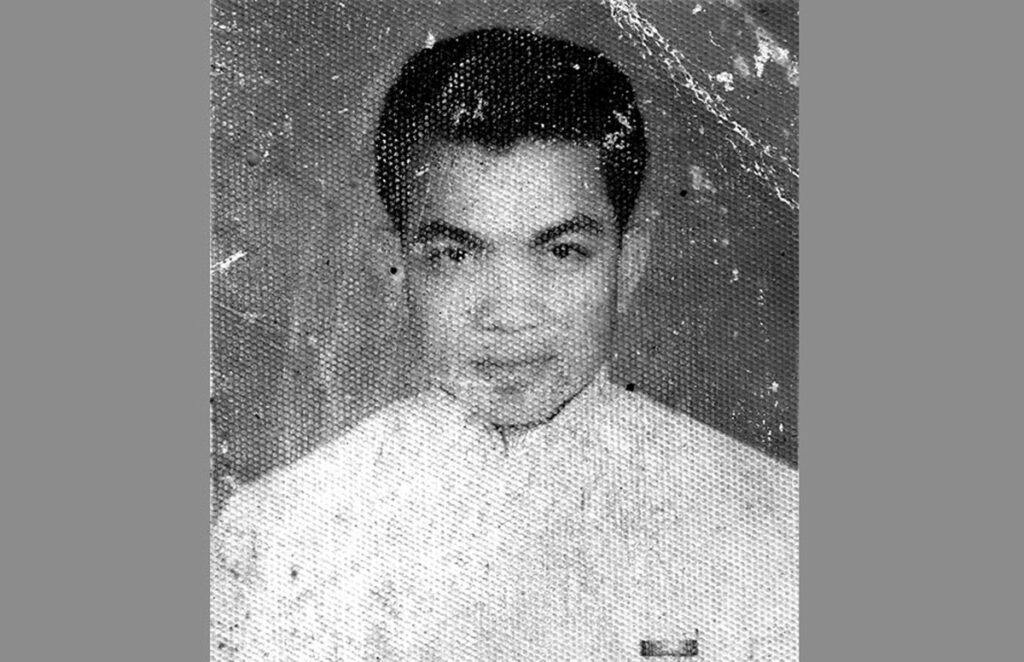

My husband and I were cousins; we grew up together in Kampong Cham Province. Our parents arranged our marriage when he was 25 and I was 18. Va was a good, gentle, and hard working person.

In 1970, Va was promoted to chief of the food services department at the Sokha Hotel in Kampong Som City. We had a good standard of living. He was even given some extra money for health expenses because there was malaria in our region.

On April 17, 1975, I heard people saying that the country was at peace. I was thrilled: I could go to see my parents for the first time in five years. On the same day, my husband went to buy medicine at the market, but found that all the shops were closed and that money was no longer used. The Khmer Rouge soldiers took his motorbike and he had to walk home.

The soldiers told us to move out of our houses so we could go to meet our parents. I believed them. Our family didn’t leave until April 24 because my husband was looking after the hotel until all the guests had left. Most of them were high-ranking people, and some were foreigners: Chinese, French, and American.

There were only a few other families on the road by the time we left. We wanted to go to our home village, but the Angkar sent us to Prey Nup. We lived in a tent for a week until we made a small hut for ourselves.

The Angkar soon began asking about our biographies. I told them that my husband was an ice seller and that I sold cigarettes. I didn’t know if they believed us or not. We were given seven cans of rice a day, one each for my husband, me and our five children. We had enough to eat at first, as they also gave us some fish, meat and vegetables.

During harvest time, the Angkar ordered us and four other families to harvest in a new village. After traveling for a day or two, we found ourselves in Koh Kong Province where the people spoke a kind of patois that I could barely understand. We lived with an old couple who were very generous; they cooked sweet rice for us.

I was assigned to transplant rice, but there were many leeches in the field. My husband told me not to scream if I was bitten; otherwise, the Angkar would send me for re-education. Eventually, I got used to them.

Va was plowing rice when the Angkar took him to be re-educated for three months in Chaeng Ko. I was worried that he was tortured or put to hard labor. On the day he returned, I could hardly recognize him. He was so skinny that his knees were the same size as his head. My husband whispered to me that if the time came when he was not with me, I must be decisive and work hard.

Our living conditions were very difficult. We had only one extra set of clothing and no mosquito net. All we had to eat was some rice soup mixed with water lily and banana bark. One day the Angkar said we could grow our own vegetables to eat. So, we put in a crop of potatoes, but then the Angkar claimed that the potatoes belonged to the cooperative. My children often cried; they wanted to eat those potatoes, but we didn’t dare pull them out of the ground.

But one day when Va returned from the rice fields, he pulled out three bunches of potatoes that were growing under the ladder of our house. I came home and was about to take a bath when I overheard him telling the children to bring me some potatoes to eat. I was terrified. I had never dared to pull out those potatoes, even though our children were starving. My husband said he would only be taken for re-education if they found out.

While he was boiling the potatoes, two village spies saw him and asked what he was doing. Va replied that he was boiling water. However, they saw that the earth under our hut had been disturbed. They returned at midnight and called my husband to catch buffaloes that were eating seedlings. He left the house quickly, taking only his karma [a traditional checkered scarf] with him. I watched him leave with two other people, an inspector and a man who had worked in Kampong Som City Hall.

Our food rations were cut after my husband was taken away. There was only one plate of rice to share with three of my children. The first to die was Sovira; she starved to death. I had taken him to the hospital, hoping they would have some milk, but they said they had run out and I should find rice soup instead. By the time I reached home with the soup, my child had died.

My two children who lived far from me were accused of being the children of a traitor. When they asked why their father was a traitor, I had to put a krama over my mouth so I would not cry out loud. If the Angkar heard us crying, they would kill all of us. I had two packages of cigarettes and gave them to a man called Uncle Sok in order get information about my husband. He said he had seen Va in prison and he was very skinny. I did not know whether Uncle Sok spoke the truth or not.

Later, the Angkar transferred the wives of the men who had been sent away to work in a village in Kampong Speu Province. It was there that my second child died. The Angkar allowed me to take her to the hospital. When the nurses saw her open her eyes, they said she was fine and did not treat her. She died with her eyes open and they blamed me, saying that I didn’t tell them.

When the gunfire began in early 1979, the Khmer Rouge chiefs ran in different directions and went back to the village to collect some rice to eat along the road. People told me not to stay there because the Khmer Rouge soldiers would return for food and would probably kill us. So I traveled to Phnom Penh and rested there a short while. Eventually we returned to Kampong Som where I had some land.

In 1982, I went to the hotel where my husband used to work. When I saw that it was damaged, it made me miss him terribly. He died for a few potatoes.