The Khmer Rouge Standing Committee aimed to ensure compliance and eliminate dissent by oppressing the people through psychological dominance. The defilement of Khmer religion, Khmer art, Khmer familiar relations, and the Khmer social class structure undermined deeply-held societal assumptions. The Khmer Rouge also destabilized the mass psychology that was secure in those realities. Cambodia’s psychology was thus altered in damaging and enduring ways. In societies that experience war and genocide, trauma significantly impacts the people’s psychology. The ripple effects of this damage are often incalculable. There are well-established statistics demonstrating a higher prevalence of trauma-related mental health disorders in post-conflict societies. this book considers the mental health implications of the Khmer Rouge era among the Cambodia populace. Specialists in trauma mental health discuss the increased rates of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and major depression, among other major mental health disorders, in the country. They also discusses the staggering burden of such a high prevalence of societal mental illness on a post-conflict society. Legal experts discuss the way in which the Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia can better accommodate victims and witnesses who are traumatized to avoid re-traumatization and to ensure a meaningful experience with justice. The text also offers a set of recommendations for addressing the widespread mental health issues within the society.

The Khmer Rouge Standing Committee aimed to ensure compliance and eliminate dissent by oppressing the people through psychological dominance. The defilement of Khmer religion, Khmer art, Khmer familiar relations, and the Khmer social class structure undermined deeply-held societal assumptions. The Khmer Rouge also destabilized the mass psychology that was secure in those realities. Cambodia’s psychology was thus altered in damaging and enduring ways. In societies that experience war and genocide, trauma significantly impacts the people’s psychology. The ripple effects of this damage are often incalculable. There are well-established statistics demonstrating a higher prevalence of trauma-related mental health disorders in post-conflict societies. this book considers the mental health implications of the Khmer Rouge era among the Cambodia populace. Specialists in trauma mental health discuss the increased rates of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and major depression, among other major mental health disorders, in the country. They also discusses the staggering burden of such a high prevalence of societal mental illness on a post-conflict society. Legal experts discuss the way in which the Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia can better accommodate victims and witnesses who are traumatized to avoid re-traumatization and to ensure a meaningful experience with justice. The text also offers a set of recommendations for addressing the widespread mental health issues within the society.

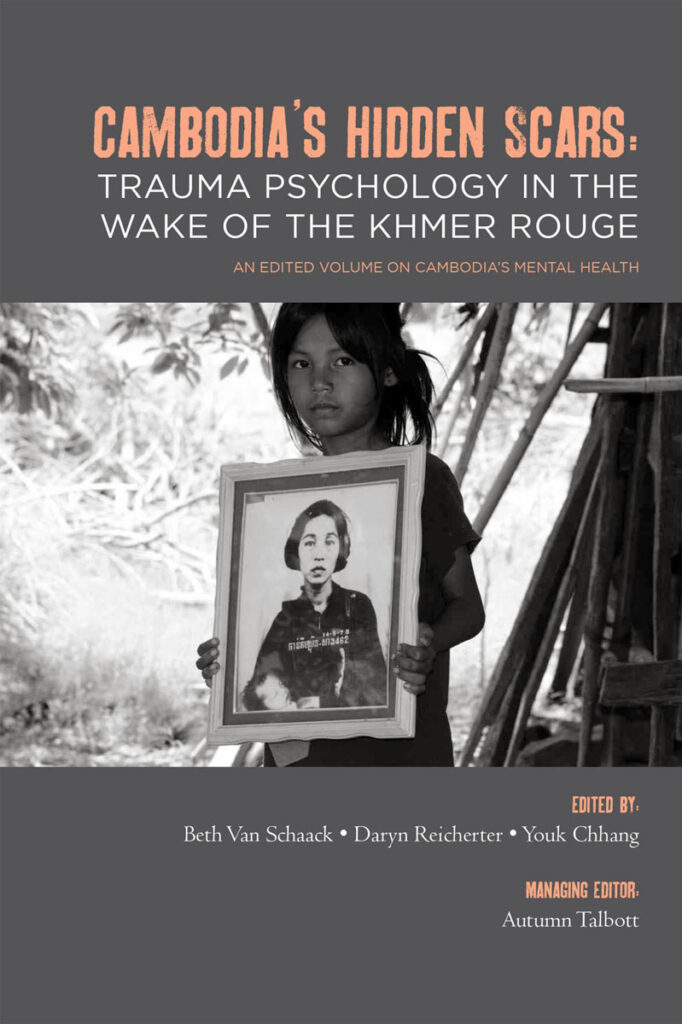

Phan Srey Leab Holds a Photo of Family Members Imprisoned by the Khmer Rouge regime (Front cover photo & caption by Eng Kok-Thay)

At nine years old, Phan Srey Leab is a quiet and docile girl with piercing eyes. She is a granddaughter of Chan Kim Srun and Sek Sat. As a member of the military, Sek Sat rose quickly through the ranks, first commanding the 18th Company of Region 33 and then the 12th Regiment in 1973. By 1977, Sek Sat was a secretary of Koh Thom district and, by 1978, a secretary of Region 25.

On May 13, 1978, the Khmer Rouge arrested Sek Sat, his wife, and their newborn baby boy. They arrived at Tuol Sleng Prison (S-21) the next day. Forty days later, Sek Sat wrote a sixty-seven-page confession, in which he admitted to traitorous activities dating back to 1965 when he joined the United States Central Intelligence Agency. According to the confession, his main goals were to oppose the monarchy and communism, and to ”hide in the revolution to build force.”

Documents from Tuol Sleng prison do not indicate whether Chan Kim Srun wrote a confession before she died. The only prison document directly concerning Chan Kim Srun is a short biography and a portrait, taken upon her arrival at S-21, of her carrying her sleeping baby. Her brief biography, obtained by the Documentation Center of Cambodia (DC-Cam), indicates that she managed a handicrafts workshop in Region 25 where her husband was chief. The portrait graces the cover of our book. In the original photo, which is on display at Tuol Sleng Museum, it is possible to see tears dropping from Chan Kim Srun’s eyes.

The two had three children together. At the time of their parents’ arrest, Sek Say was eleven and her younger sister, Chreb, was only nine. While the newborn son was imprisoned with Sek Sat and Chan Kim Srun, both of the girls and their aunt were jailed in a low-security prison in Koh Thom district. Chreb & Sek Say escaped with the aid of the Vietnamese in late 1978, but Chreb died of disease before reaching safety. Sek Say survived and moved to Kampong Speu where she remains today in Kong Pisey district.

Sek Say resembles her mother. She has five children, of which Phan Srey Leab is the third. Srey Leab likes to play in the kitchen when she can find a spot of her own. After school, she helps her mother cook, do household chores, and look after her younger sisters. Srey Leab only manages an average performance at school.

Srey Leab has heard her mother blame their poverty on being orphaned at a young age. The young girl asked once about her grandparents and what had happened to them. Srey Leab listened to their story, but—quiet as she is—she has never again talked about it.

Funding for this project was generously provided by the United States Institute of Peace (USIP) with core support from U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) and Swedish International Development Agency (Sida).