Noeun studied in Kandal Province. He was a good student and earned a diploma. During the chaos following the 1970 coup d’état, he volunteered to join a unit that guarded his school at night because they were afraid the Vietnamese would burn it down. He wore a uniform that was the same color as tree leaves and carried a gun. Although he was paid 500 riel a month for this, it wasn’t enough for food.

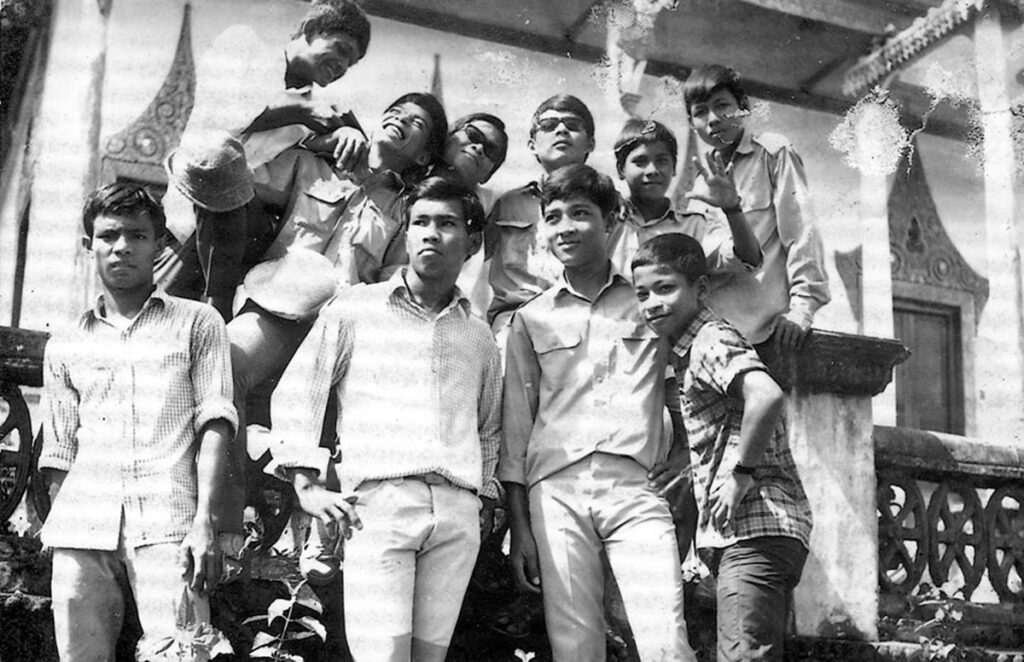

In 1972, many bombs fell on our village, so Noeun went to Phnom Penh. He volunteered to join the Lon Nol soldiers there, and two years later was sent to military drills in Long Hai Province, Vietnam, for three months. Whenever he visited home, he would stay only two or three days. Once he came home and brought us a stove, photos and sarongs.

Noeun was then transferred to Battambang Province with two or three of my cousins; he was made a second lieutenant in the Air Force. He married a girl there named Voeun; she was a teacher from Svay Sisophon. We didn’t know he was married at first because communications were cut off during the war, but we later heard this news from my cousin who worked in Battambang.

Noeun was working in Phnom Penh when the Khmer Rouge evacuated the city. He tried to come home to our village, but the road was blocked. So Noeun sold the clothes he was bringing us and he and his wife went to her parents’ village in Battambang. The Angkar there assigned him to carry rice and corn to the cooperatives.

One day in 1976, the ox cart he was driving overturned. The group chief complained to the Angkar about it, saying that by destroying the cart, he was destroying the Angkar. He added that Noeun used to be a second lieutenant in the Lon Nol army. Then the cadres arrested him and took him off to be killed.

His wife Voeun waited a long time for his return. Then the same unit chief asked her to marry him, saying he would kill her and our families if she refused. Intimidated, Voeun agreed. Her son with Noeun was two years old at that time.

Voeun sent photos to my family, and we came to know her through them. Later she paid a visit to my hometown in Kandal Province. She told us that she divorced her second husband after the Khmer Rouge were overthrown. Although they had two children together, he was a gambler and ran through all their money.

My second brother Noem finished high school in the Lon Nol regime and then studied medicine in Phnom Penh. Just before Khmer New Year in April 1975, he visited our home. He had only intended to stay for a day, but the Khmer Rouge soldiers would not allow him to leave. So he stayed in the village and after a year, the Angkar chose him to be one of their village militiamen.

One of his friends who had studied with him reported to the Angkar that Noem was educated and knew both French and English. This created problems for us; I had one brother who was a former Lon Nol soldier and one who was a Khmer Rouge.

The Angkar assigned him to be a messenger; he carried telegrams because we had no telephones then. One day they lied to him, saying he should go harvest rice far from the village. My nephew, who went with him, said they took him off to fight with the Vietnamese. My nephew fled from the battlefield and came home, but Noem found it difficult because he was carrying telegrams; there was a lot of shelling and if he had been caught running away, he would have been arrested.

My parents, brothers and sisters waited for him, but the wait became longer and longer. After the collapse of Democratic Kampuchea, I went to a fortuneteller and asked about my brothers. She said they would not return, so I have lost hope of ever seeing them again.