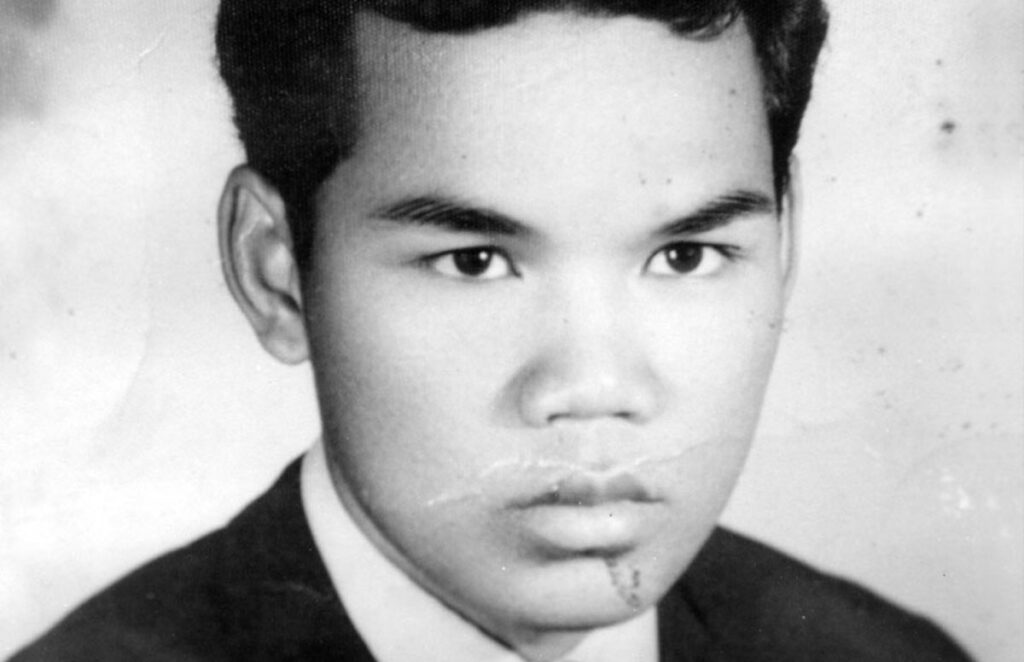

was not really ready for love when I was 18. Mann and I first met on the Khmer New Year, when he was on a short leave from the army. It was love at first sight for him. And when he had his unit chief ask my mother for my hand in marriage, I didn’t have any feelings of love for him. But I had to accept my parent’s arrangement for me. His chief and Lay Sam, a colonel in Unit 554, were at my wedding, but not his parents.

Between 1972 and 1973, people fled from our village in Kandal Province because they did not want to join the Khmer Rouge. My family moved close to my husband’s military base where the American soldiers were distributing food.

Being a soldier’s wife was very difficult during that time. I packed food in a palm leaf box and brought it to my husband on the battlefield, although he told me not to risk my life to do this. As the Khmer Rouge soldiers were coming closer, the Lon Nol soldiers lost their courage and put up white flags; they knew they could not win. Mann was then able to return home to me and the children.

My family tried to go to Phnom Penh on April 17, 1975, but we were not allowed to enter the city; they said the American Air Force would be dropping bombs there soon. My father desperately wanted to go to his home village; he was an educated man and thought they would give him a position there. He asked some villagers if we could go with them by truck. I said to him “Dad, it won’t take that long to walk to our home village. If you want to go by truck, just go alone.” Dad was very cross at me and the rest of our family for not listening to him. He got on the truck, but it headed to Battambang Province instead. His ambition had failed, and my father disappeared.

In the cooperative, my one year-old daughter hardly ate anything and had dysentery non-stop, so I took her to the hospital. My mother Im Pok took turns staying with her. The medical cadres gave my daughter an injection; my mother said she died horribly. She wanted to bury her granddaughter, but a teenage nurse took her body away and did not allow my mother to go along. When I heard that she had died, I ran to the hospital, but I was too late. That day, my portion of rice soup was given to other people.

Our village’s rice ran out within a year and our family was scattered. Sometimes, we were able to reunite, and my husband always tried to bring food for the family. Mann could not swim and once risked his life to cross the river during the rainy season to find some vegetables for us. He almost drowned, but his younger brother saved him. His effort paid off, though: he got a big jar of salt and two military uniforms from generous villagers.

I always claimed that my husband was a poor farmer whenever the Khmer Rouge asked about his biography. But keeping a secret was not enough, for the Angkar had many connections and asked them about my husband. In July 1977, he was sent to cut trees. When he left, he said, “If I do not come back in a few days, I probably have been caught or tortured by the Khmer Rouge soldiers. If this happens, I will commit suicide. Do take care of our children well.” I was seven months pregnant then. After a week his clothes came back to the village for other people to wear. I recognized them because I had sewn them myself. Two months and five days after my husband was taken, I gave birth to a son.

The Khmer Rouge nearly killed me because I was too inquisitive about my husband. “When will my husband come back home?” I asked the unit chief. The local people whispered that comrade An would be sent to live with her husband if she kept asking like that. A base person named Loeng told me not to ask about my husband again, or I would be killed, and that Mann had been sent to Sa-ang Prison. I dared not ask again after that.

When the Khmer Rouge regime collapsed, I was lucky. I survived.