My mother died when I was too young to remember and my father died when I was ten. Thus, I grew up to be a very independent person. After the death of my father, my godfather, who was a district chief in Kampong Thom Province, asked if he could adopt me. He died when I was 11, and my godmother died when I was 15.

Then I met a monk along the street in Kampong Thom. He said, “You have no mother, no father. You can go with me to Phnom Penh.” So I went with him and lived in a pagoda there for a year. I graduated from Tuol Svey Prey High School; it later became Tuol Sleng Prison.

While I was studying in college, I took part-time jobs like selling bread and driving a cyclo to earn extra money. I also studied French and got a black belt in judo in my spare time. When I was a third-year student at the Faculty of Commerce, I began working at the Khmer Commercial Bank and teaching judo.

I had family, no neighbors to guide me, so I became very exact about living, and realized I had to do anything necessary to survive. I didn’t have any luck in living, but I was very resourceful. I struggled so I could have luck in the future, and kept struggling when I was imprisoned.

On April 17, 1975, I was at the bank preparing some documents when my colleagues and I got a strange feeling. We looked out to see soldiers wearing black uniforms; all of them had rolled up the right legs of their trousers and were carrying guns. They entered the bank shooting and forced all of the staff outside. Many of my colleagues and I left without locking our rooms.

On the way out of the city, the Khmer Rouge made an announcement on a loudspeaker: “The Angkar needs educated, technical, and high-ranking people from the Lon Nol regime help rebuild the city. It will take time for the Angkar to re-organize the country.” Many people – most of them men – were registering their names. The Khmer Rouge even gave them rice, dry fish, pork, and bread to encourage them to register.

I spent the next month in a pagoda in Kien Svay District, growing more hopeless each day. When the rainy season began, the Khmer Rouge began dividing people. Some stayed to work in the rice fields, while those with relatives in the provinces moved on. Some of the rich Chinese families had always been in Phnom Penh and had nowhere to go. They drove their cars into the river and killed themselves.

I had nowhere to go as well, so I traveled across the Neak Loeung River. At the border of Prey Veng and Svay Rieng Provinces, I decided to throw a rock into the air. If it stood up when it landed, I would head to the East Zone and if it fell over, I would head to the North Zone. The stone fell straight down, so I turned to the east.

When I came to Kampong Soeng Subdistrict, the Khmer Rouge forced all the people there to sit for the whole day without any food or drink. Then they started noting down people’s biographies. I decided to tell them I was a student.

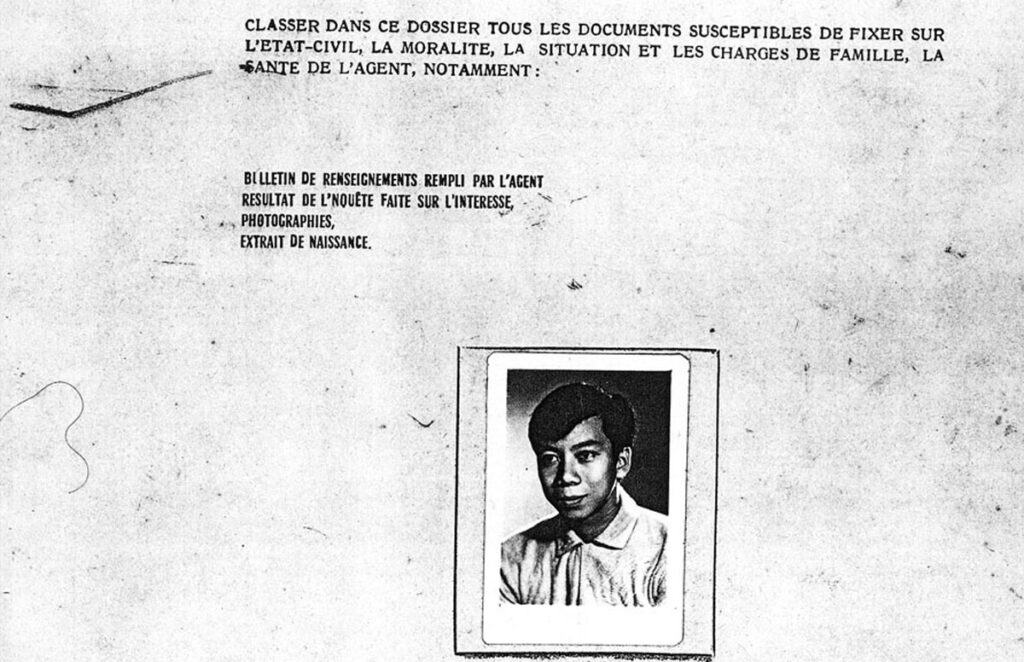

I had also taken the name of the people who adopted me, and was known as Kong Meardey Pheak Kday. Khmer names have only one or two syllables. But in the Pol Pot time, if you had a long name, it meant you were not a Khmer person and must die. So from then on, I only used the name Kong Meardey.

The next day, the Khmer Rouge soldiers said we needed to be re-educated. A cadre with wavy hair announced, “All our friends have been lucky. The Angkar wants to educate you. Don’t take any belongings with you because the Angkar has everything you will need.” We were put in rows with an armed soldier walking behind each row. They then took us to Porng Toek security office in Prey Veng Province. After taking our biographies again, they put us in an office and locked the door from the outside. The only thing inside was a metal ammunition can that we used as a toilet. It was then I realized that I was trapped.

There were 518 prisoners in the security office; most of them were former students, teachers, and Lon Nol soldiers. At night, we slept opposite each other. Our legs were chained with a long piece of metal which was locked at the end. In the ten days I was held there, the Angkar sent away the high-ranking people, while the others were sent to work. I worked in the road building section; it held 50 prisoners. We walked an hour to our worksite, where we dug earth every day from 5 a.m. to noon and then from 1 to 6 p.m., with only one can of rice to eat. All the prisoners worked hard day and night because the Angkar declared that when we finished the road, they would release us.

But they lied to us and our hopes were for nothing. Instead of releasing us, they sent us to a new work site to dig canals. It was the rainy season, and we slept by the canals; I was so tired that I fell asleep in the rain. They also reduced our rations, so many of the prisoners got very sick and died from overwork.

Next, I was ordered to find vegetables for the cooperative and got better food. At night, I would massage the chief cook and other cooks in the unit in exchange for a little food. I tried my best to please them and even told the Angkar that I used to be a masseur. When I lived in Phnom Penh, I used to a judo trainer, so I knew about the structure of the human body. One night, a man said the Angkar wanted to meet me. I was very scared. When I walked into the office, Khmer Rouge chief asked me if I could massage his twisted ankle. I held it tightly and poured snake oil on it mixed with charcoal ashes. Then I pushed the bone into alignment. After that, they gave me full food rations.

At the end of 1976, when we had finished digging the canal, the Angkar called a meeting and released many of the prisoners at the security office, including the women. But the rest of us were sent to a new construction site in Prey Veng Province. We walked there along National Road 1. Many of the men were very happy; they hadn’t seen a road in a long time. We walked in one line; if someone stepped out of the line, they were beaten. Our jobs at the new site were to build dikes for the rice field, work in place of farm animals in plowing the fields, and dig canals. They beat us if we stopped work; the overseer would laugh and make the prisoners count the number of time they were hit. He beat two prisoners to death for drinking water from the canal. The soldiers removed their livers and cooked them to eat.

I nearly starved to death at that site. Sometimes, I snuck out to find frogs, crabs, snails, lizards and mice to eat. But they caught me and beat me with bamboo branches until I bled. There were a lot of flies that year, so whenever we ate something, we had to keep our mouths closed. One by one, the prisoners died; some died in their sleep, some while walking, some were executed, and others hung themselves. Some people were so hungry that they ate the dead bodies.

On November 30, 1976, the Angkar made all of us stand in a line. The cadres said that nearly all of the prisoners now believed in and respected the Angkar, and they would be sent back to the base. But there were twenty prisoners who were not yet educated enough. I was among the twenty. Later I overheard the cadres saying that those who were released were killed.

A little while later, the security guard called all twenty prisoners to stand in a line. Six Chinese-made cars pulled up and we climbed in. The Angkar told us we were lucky; we were being sent back to our base village. I began crying and every one of us gave thanks to the Angkar. I had been in prison for one year, six months, and six days. Of the 518 people in that prison, only 20 of us survived.