Before I was born, my father was a teacher in Pursat Province, where he fell in love with my mother Kang Sophat; she was the daughter of merchants. She studied until Baccalaureate I and then quit school to help her parents sell goods in the market.

My grandmother arranged for my father to take another wife when my mother was pregnant with her second child. She and the new wife had babies born on the same day.

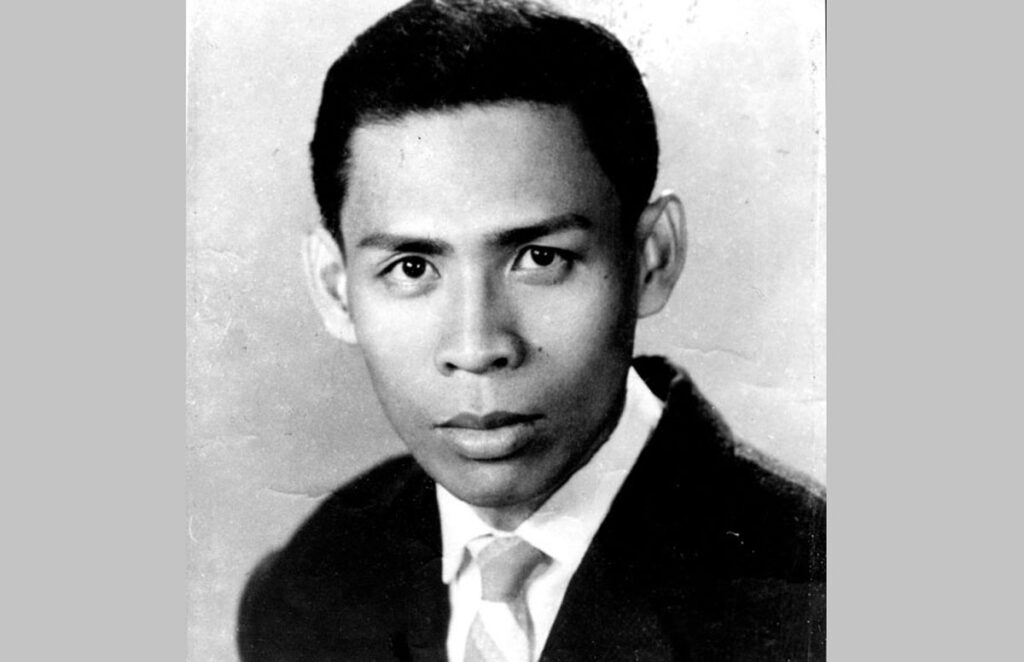

I was born when my father was teaching in Kratie Province. My parents gave me the name Buoy Somacha, but called me Map because I was fat when I was young. Our family moved wherever he taught. He was able to us on his salary as a teacher.

My father quit teaching during the Lon Nol regime and ran for Parliament. But he lost, so we moved to Phnom Penh. There, he opened a printing company across from Olympic Stadium and a newspaper called Khmer Benefits, which was distributed nationwide. My father was a very good spokesman; he liked talking and he liked writing. Later, he was imprisoned for a year because he wrote an article opposing a Lon Nol policy. My father re-opened the printing house after he was released from prison and started another newspaper called Rescue Khmer. The paper was only open for a week when the Khmer Rouge soldiers took control of Phnom Penh.

Some of my father’s friends who lived in America told him to flee there, but he refused. He had nine children to support and was arranging for my older sister’s marriage.

When the Khmer Rouge evacuated the city, they said they would establish a new system in Phnom Penh and that people could return in three days. Because my father was a journalist, he knew what was really happening and did not believe them.

My family put all our belongings in our car and started out for Prey Veng Province. Part way there, the Khmer Rouge claimed that people who drove cars were feudalists and oppressed the workers. They would not allow us to go any further in an automobile, so my father pushed the car into the river and we continued on foot. Two days later, my family reached Prey Veng. We had eaten all the food we brought from home, so we exchanged some of our clothes for rice.

When we reached my father’s hometown, he tried to hide his identity by saying he was a farmer. He knew how to fish, make tables, and farm, so there was no problem for a while.

There was much jealousy between the local people and the April 17 people. For example, everyone was supposed to share food equally. Some people did this, but usually, the April 17 people got less food than the local people.

My mother delivered a baby at a time when there were not many medicines; mainly, they had what we called “rabbit dropping medicine.” There were no trained nurses or doctors, either. My mother died during childbirth; she bled to death. The Angkar did not allow my father to give her a funeral, so he buried her deep in the jungle.

Her baby boy lived. We named him Samnang. Because Samnang did not have any milk to drink, my father asked the villagers to adopt him. The couple who took him really loved Samnang and regarded him as their own son.

In 1976, a man named Loeut secretly assassinated the village chief. The Angkar wasn’t able to find who did this, so they asked my father and other men in the village to move to another location. Several men took him away during the night. He was wearing a striped shirt and had a large checked scarf around his neck.

I think my father realized that something bad would happen because the villagers knew he used to work in Phnom Penh. He told us to run away from the village if he did not return and to take care of the family’s photographs, which I buried in a jar and covered with garbage. I think he was then ready to die, and we never saw him again.