Of my parents and thirteen siblings, only two of us survived the Khmer Rouge regime. Nearly all of them died in 1977 from starvation and illness.

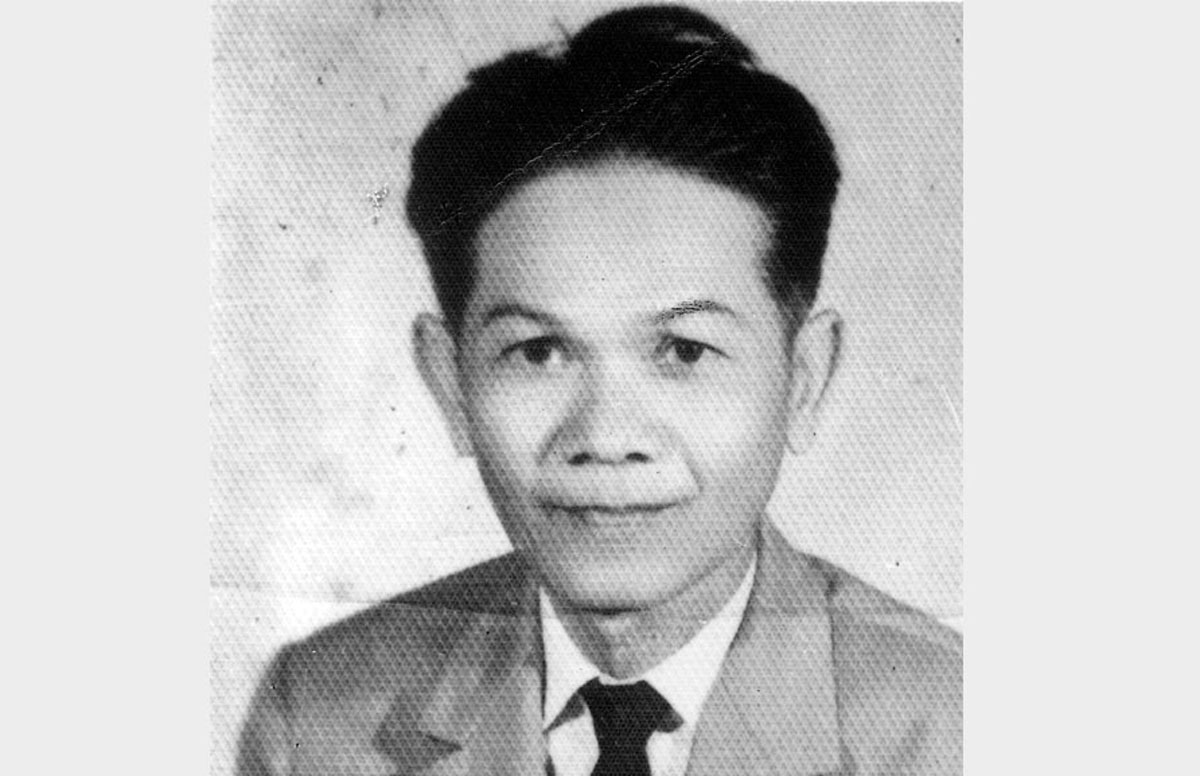

My father was a serious, responsible man who did not talk a lot. He was born to a very poor family with many children, and lived in the pagoda when he was growing up. His mother was often sick and he had many difficulties because he was always borrowing money to find cures for her. So, he decided to study medicine, a subject which he loved. He was an outstanding student in both in science and French.

My father worked very hard in order to support his 14 children and was promoted often. We lived in a big house because he earned a lot. In addition to working at the mental health hospital at Prek Tnot, he had a private practice so he could earn additional money. My mother grew some vegetables at home and then sold them at the market in order to help support our family.

As the 1975 evacuation drew near, there were so many shootings and bombings each night that my father was barely able to sleep. He would often stay at my youngest sister’s house in Phnom Penh, while my mother lived with my sister in Kandal Province. He left the house on April 17.

By the time he arrived, my mother and my other siblings had already left. He knew that my mother had taken all the children to her hometown in Sa-ang District and met us there. But we could not live happily in her village because many people there knew we were well off.

Our family was then sent to Kampong Chhang Province. My father had to work very hard without enough food. He was old, so he could barely endure the difficulties he faced. One night, he decided to steal some ripe mangos behind the Khmer Rouge military office. I tried to stop him, but he would not listen to me. He was lucky; it was a dark night with heavy rain and he wasn’t caught. He brought ten ripe mangos for the children who lived with him. Five of my brothers and sisters worked near the Cambodia-Thai border and starved to death one after the other.

Many of the people in the village where we lived began dying of starvation in 1976. In 1977, food was short and the Angkar did not give us any rice for three days. My mother exchanged her jewelry for rice, fish, and fish paste. When all of her jewelry was gone, my father died from starvation. My sister wrote his name on a piece of paper and put it in a bottle; we buried it with him. She wanted to make sure that if any of us survived, we could find his bones one day and hold a ceremony for him. My mother died a month later from a broken heart.

At the end of 1978, some villagers who listened to a radio said that Vietnamese soldiers were liberating Cambodia. The Angkar ordered my mobile unit to dig a hole for storing rice, dry fish and salt. The people who had worked in the previous mobile unit were shot after they completed their work. So after we had dug the hole, we began running.

I traveled across the jungle for many days until I reached Kampong Chhnang Province. I even hitchhiked with Vietnamese soldiers. After living with two of my aunts for nearly a year, I returned to Kandal and saw my older sister, who had just come out of the jungle.

My sister and I have still not been able to locate our father’s bones; there are too many mass graves in the area.