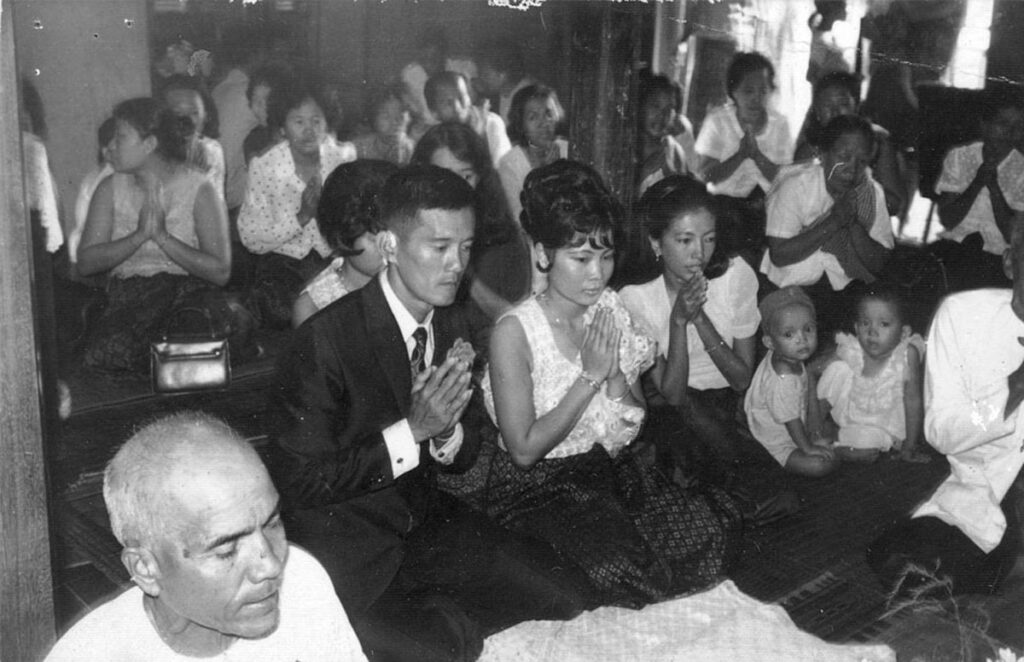

When my father returned from studying at a military school in Indonesia, he was promoted to the rank of major in the military police. My mother was a teacher in Phnom Penh. They met before my father went to Indonesia. After he came home, he proposed to her.

In 1974, father was transferred to Battambang Province where he was in charge of all the military police there. My mother and I moved with him and she taught at a pagoda.

The Angkar began following our family’s activities shortly after they took control. When they learned that my father was in the military police, they asked him to greet King Sihanouk near Thip De Mountain, saying the King was visiting there. My father, along with many other military police and Lon Nol soldiers, was taken to greet the King. Three or four cars full of people left that day; it was the last we ever saw of him.

After the Khmer Rouge regime collapsed, I met a man who had also been a military policeman and was put in the car with my father. He told me that when the cars came close to the mountain, they heard gunshots coming from the jungle. The Khmer Rouge took guns and shot them, he said. Although this man was able to escape, my father and most of the others had been killed.

Next the Angkar began spying on my mother. When she and several friends who had also been teachers before the Khmer Rouge regime realized that they were on a list of people to be killed, they asked my mother to run away with them. She could not take me along with her because it was a long and dangerous journey.

She decided to leave me with a woman who is now my foster sister; her name is Sorn Si Yem; her younger sister had been one of my mother’s students. Mother said to Yem, “Please don’t change my son Kinal’s name. If I have a chance to live, I will come back to take him from you.” I was sleeping when she left, but Yem said my mother kept crying as if she did not want to leave me, then walked several meters before stopping to run back and take one last look at my face.

I hide myself anywhere I could after my mother disappeared because the Angkar accused me of being the son of an enemy. At night, Yem stole leftover rice and fish paste for me. She boiled the rice and had me drink it, and sometimes gave me sugar. I ate under the bed, but I was still starving.

Yem was a medical worker, so sometimes she stole the water the hospital used for cooking rice and added lotus leaves to it. A lot of people died in the hospital because there was no medicine and they became swollen. Their bodies were buried in shallow graves and covered with tree leaves. The dogs dug up the bodies sometimes; it smelled terrible.

One day, the cooperative chief’s wife went into labor. Several midwives were sent to help, but they could not, so the cooperative chief sent them to be killed. He then threatened Yem with death if she could not help deliver the child. Yem cut a small piece of sangke wood and burned it as incense while praying for success in delivering the baby. When the baby was born healthy, the chief thanked Yem and gave her a lot of rice as a reward. Yem is still a midwife today.

The Angkar took Yem to be re-educated many times for hiding the son of an enemy. They wanted to kill her, so Yem gave me to her mother who lived far from Yem’s village. And I changed my name to Sorn so the Angkar would not find me. We moved many times after that, but I stayed with Yem’s mother until the end of the regime.

After the collapse of the Khmer Rouge regime, I lived with her in Battambang Province. But I am still waiting for my parents to come back, especially my mother; I believe that she is alive.