On Trial: 16 Years of the ECCC Process

By Dr. John D. Ciorciari

Senior Legal Advisor to the Documentation Center of Cambodia

Dean of the Hamilton Lugar School of Global and International Studies, Indiana University (USA)

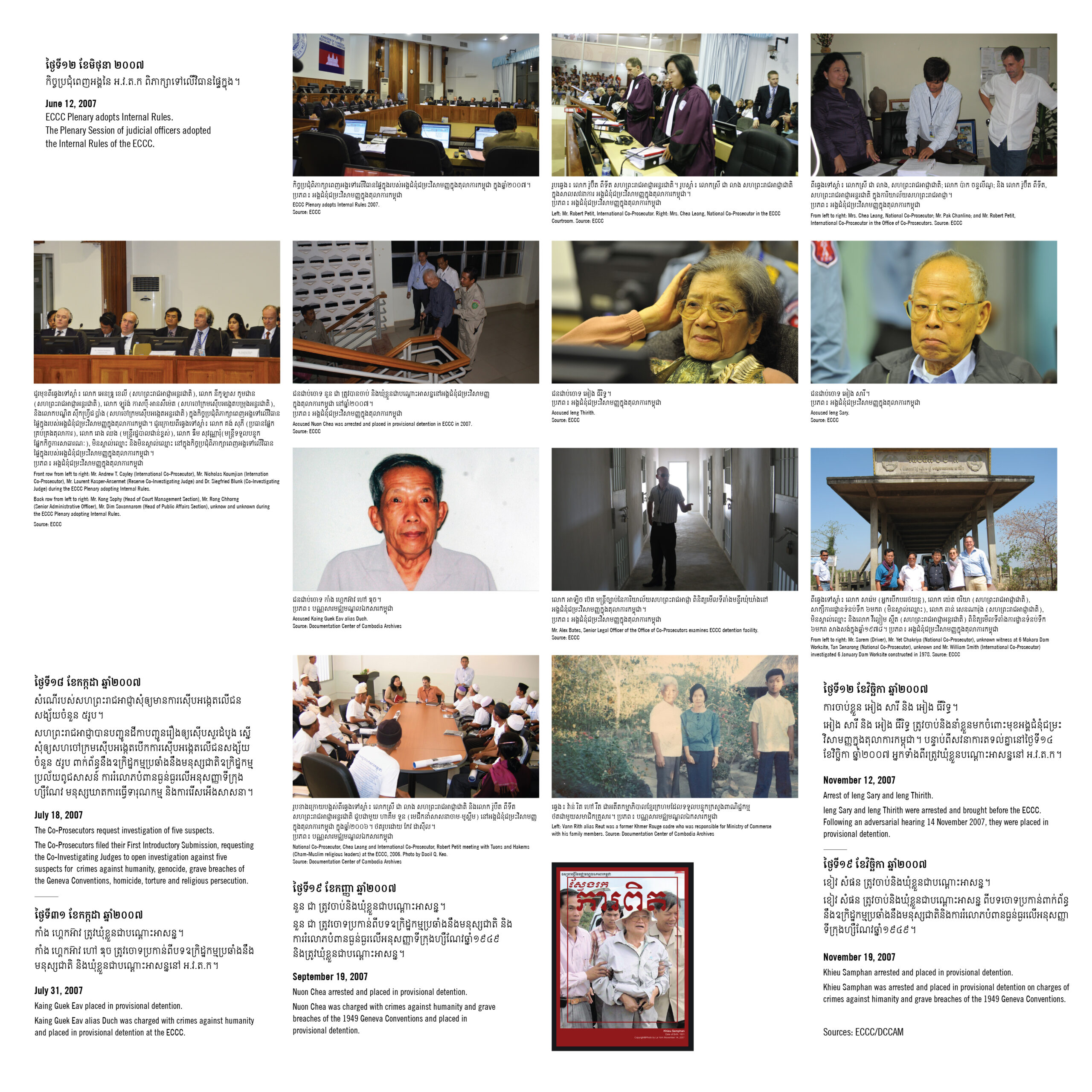

In the decades after the demise of the Khmer Rouge regime, Cambodia suffered from almost unfettered impunity. The architects of some of history’s most notorious mass crimes went free, unchallenged by a credible legal process. Survivors bore their pain with little prospect of justice. Their hopes rose with the 2004 establishment of the Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia (ECCC), a tribunal organized and staffed by the Cambodian government and United Nations. The ECCC was created to deliver justice from some of the most notorious Khmer Rouge atrocities, including genocide, war crimes, and crimes against humanity. Cambodian survivors overwhelmingly welcomed the tribunal as an opportunity to advance truth, justice, and reconciliation.

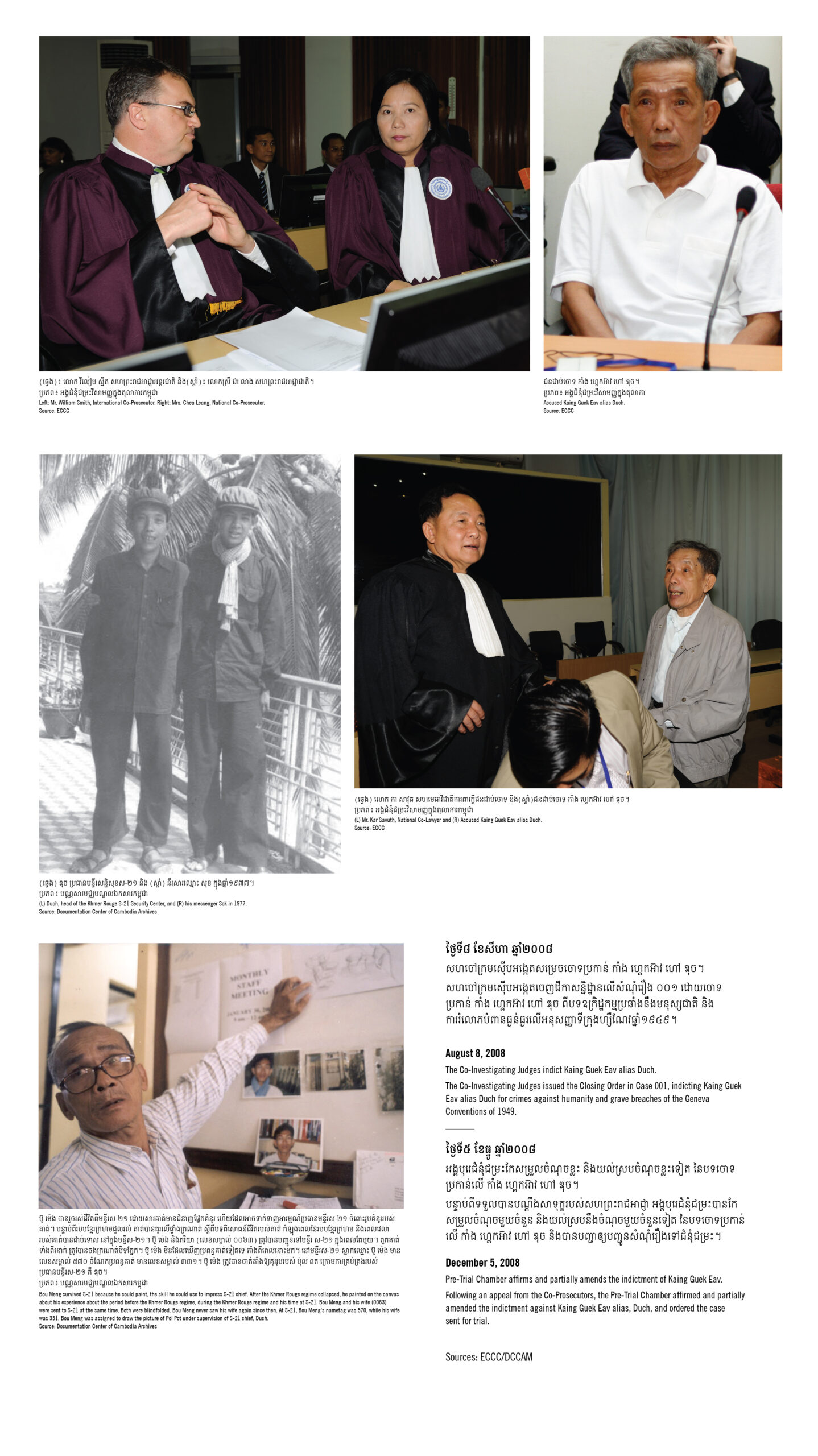

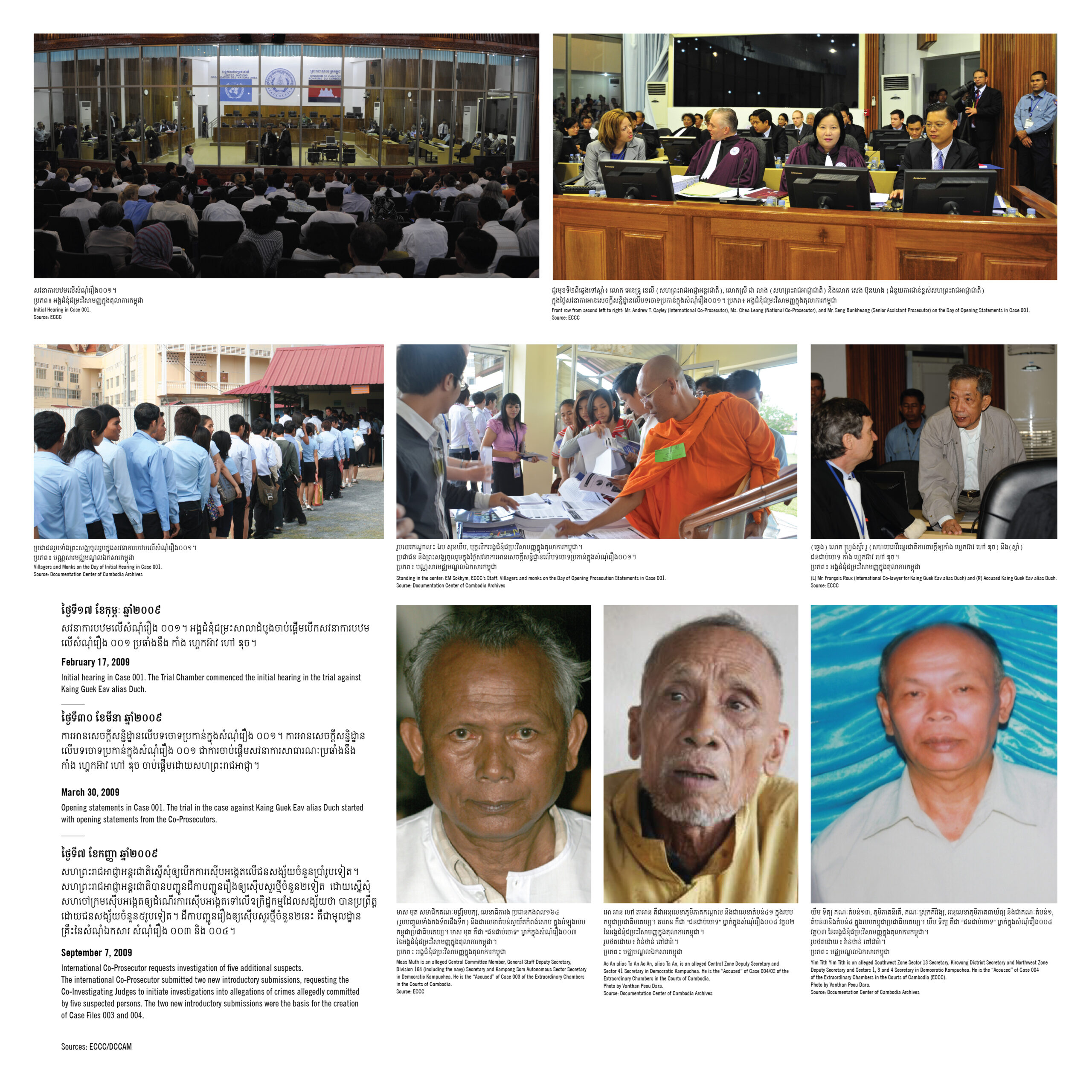

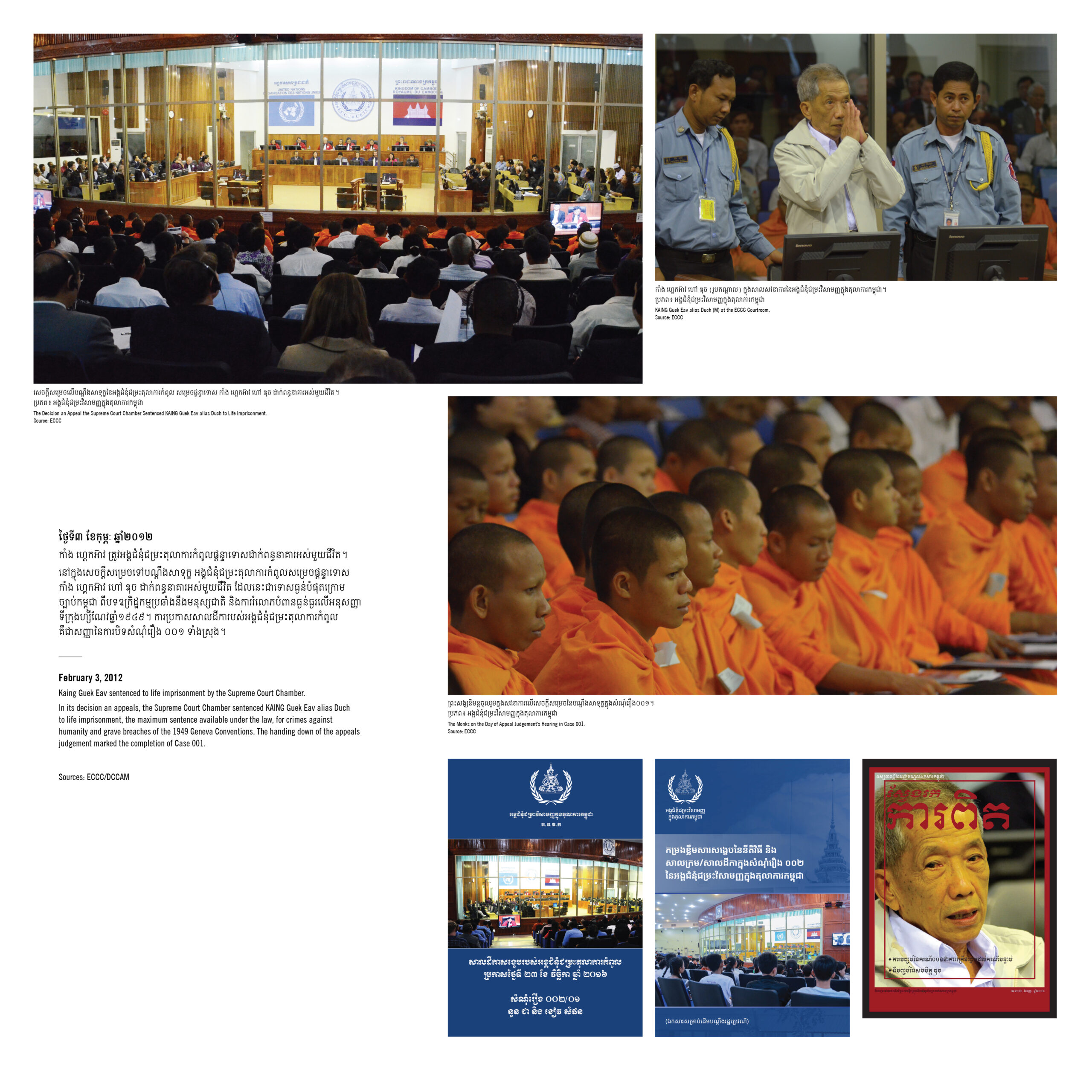

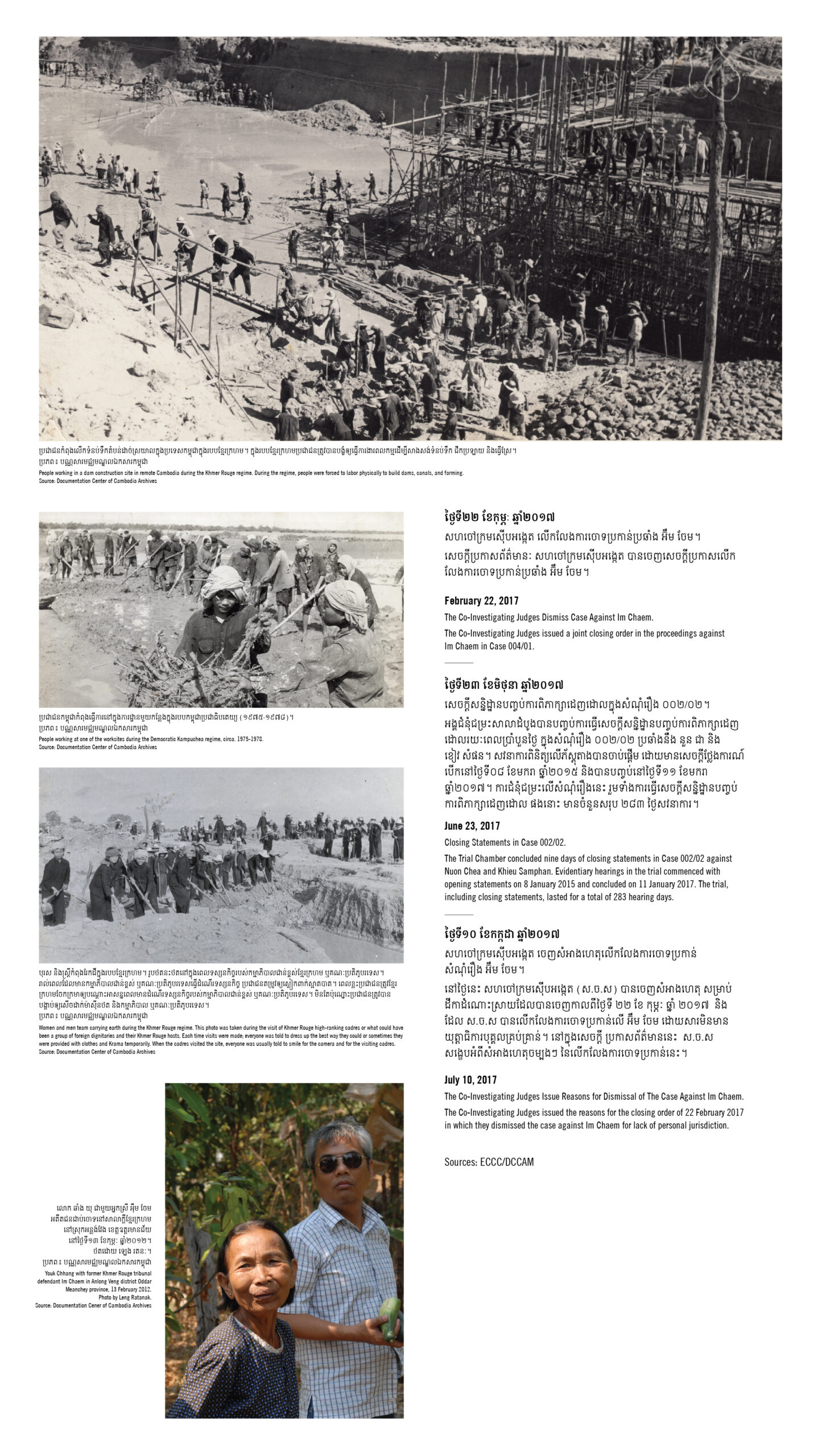

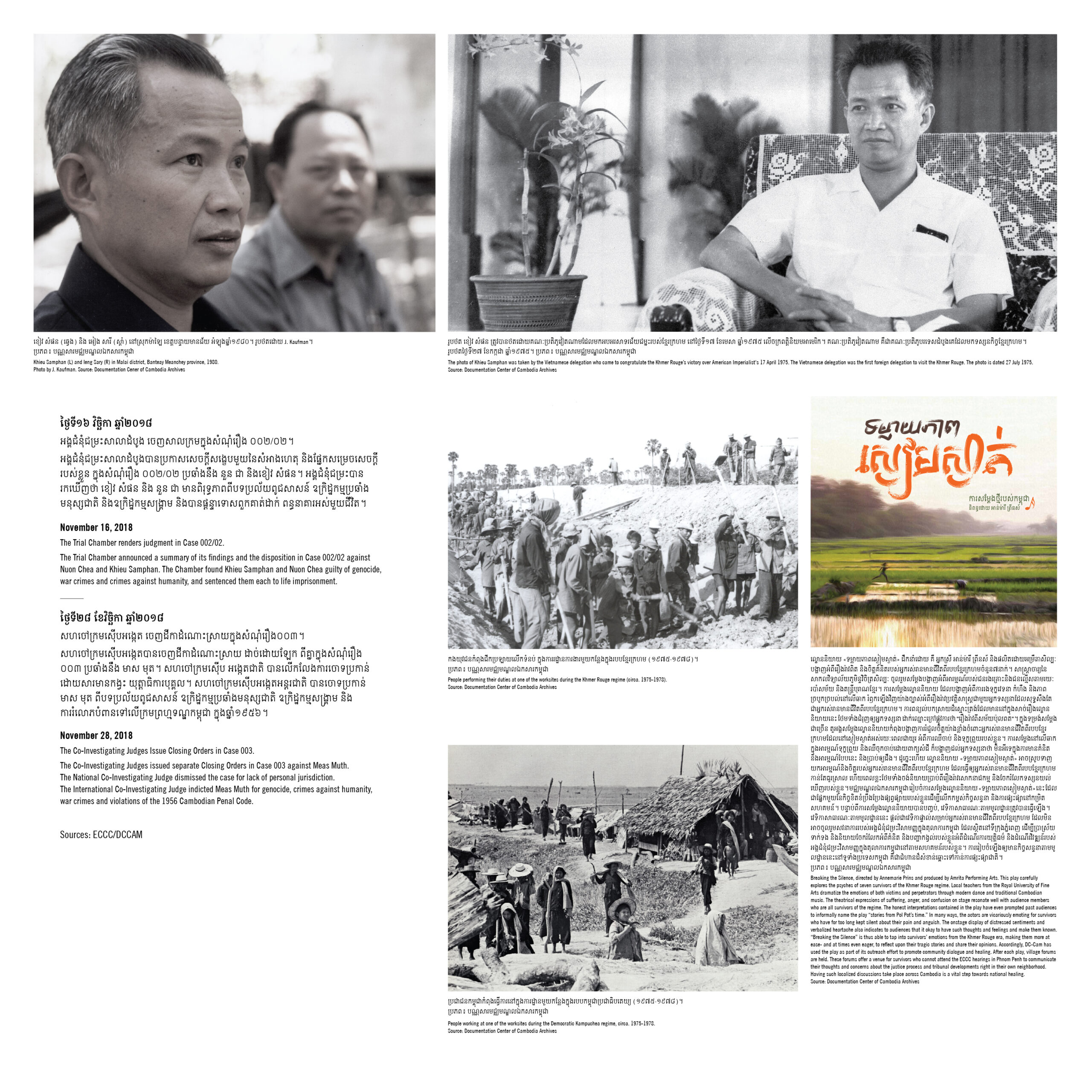

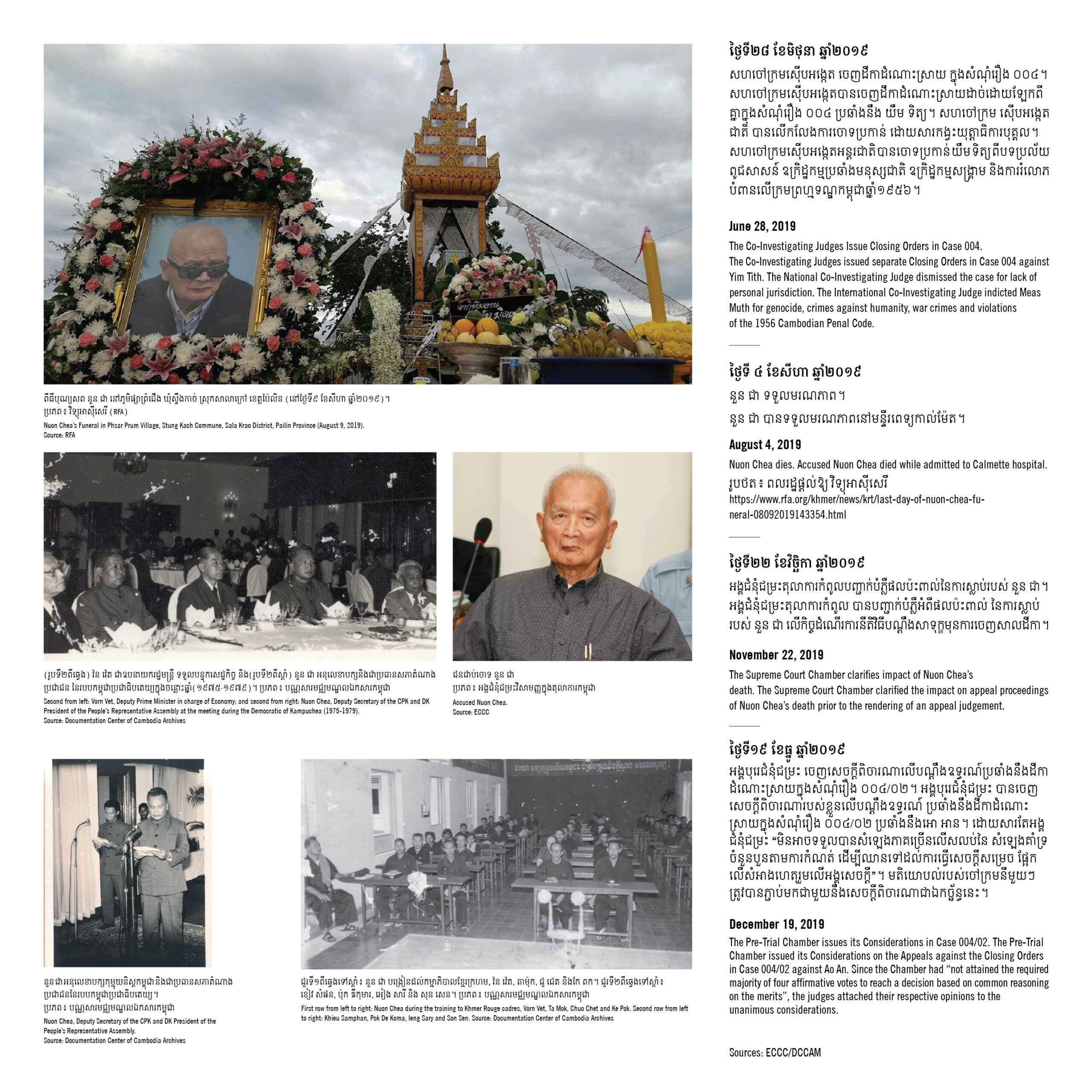

The ECCC process unfolded over several years. Cambodian and international prosecutors, investigators, judges, lawyers, and staff devised a complex set of rules and procedures to govern the complex “hybrid” court. Investigators then set out to probe some of the many crimes of the Khmer Rouge regime. Its first case focused on atrocities at the infamous S-21 security center at Tuol Sleng, led by Kaing Guek Eav, better known as Duch. His lengthy trial featured a great deal of documentary and forensic evidence, as well as testimony by expert witnesses and a number of courageous Cambodian survivors. In 2010, the ECCC convicted Duch for crimes against humanity, murder, and torture—the first credible judgment in more than 30 years for the atrocities of Democratic Kampuchea (DK).

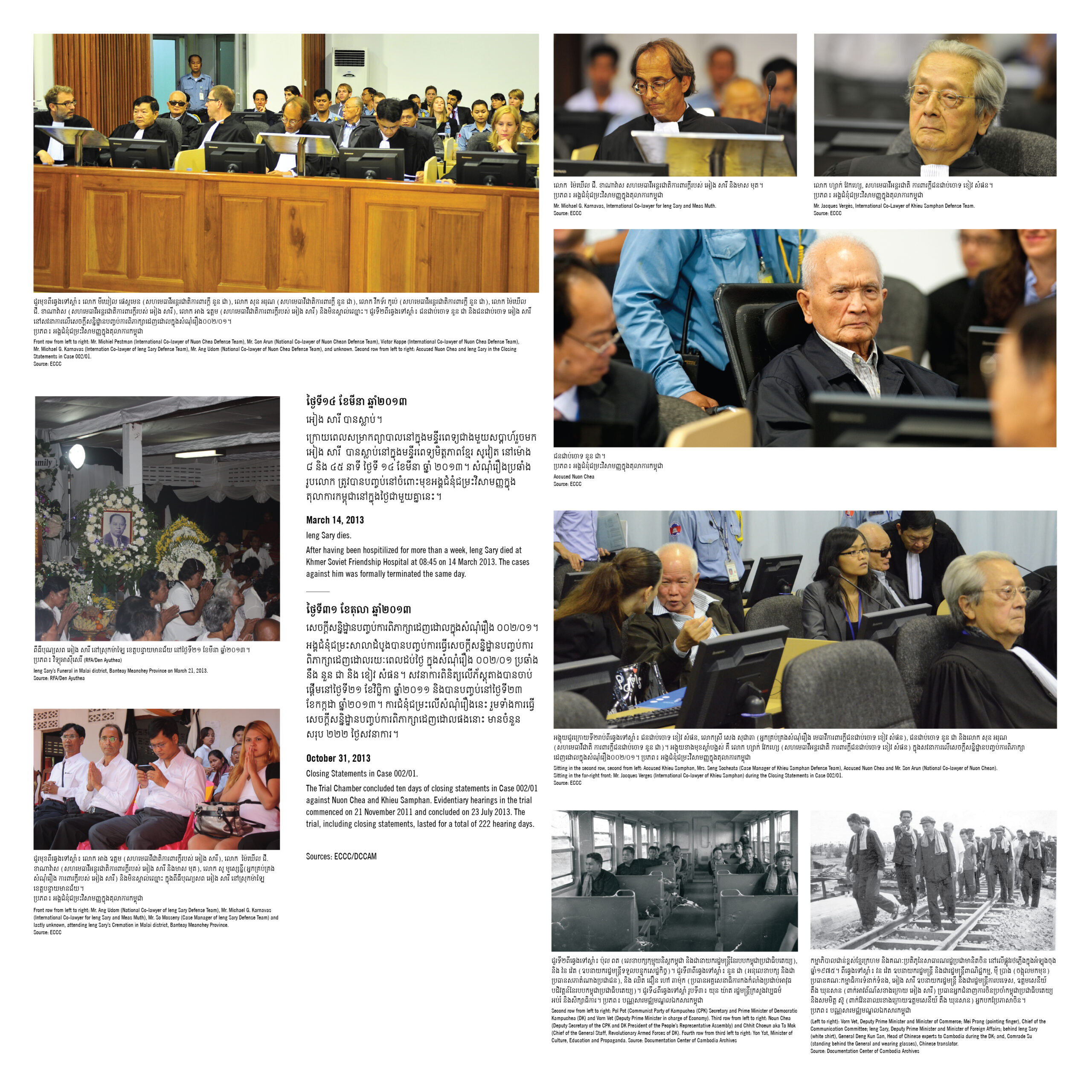

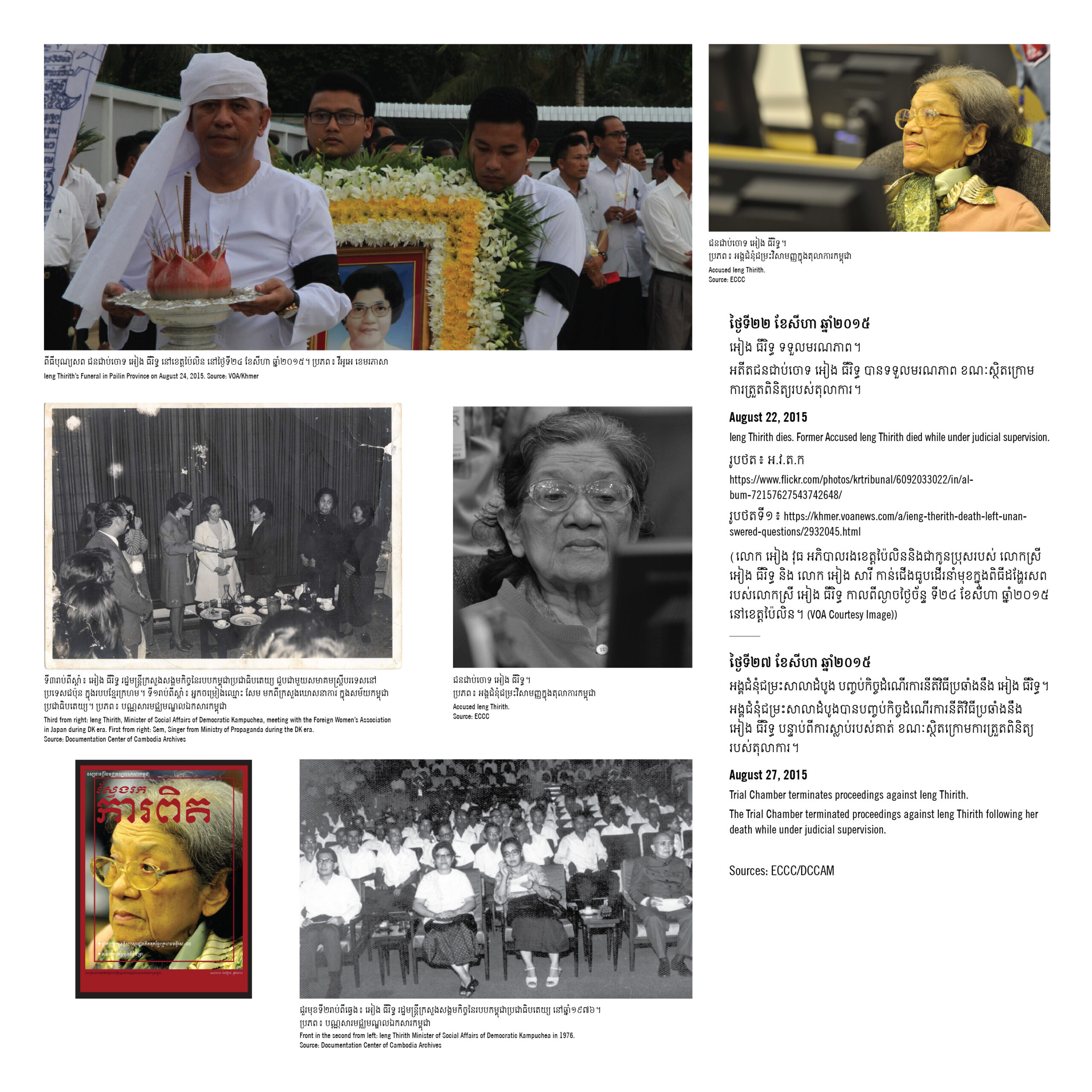

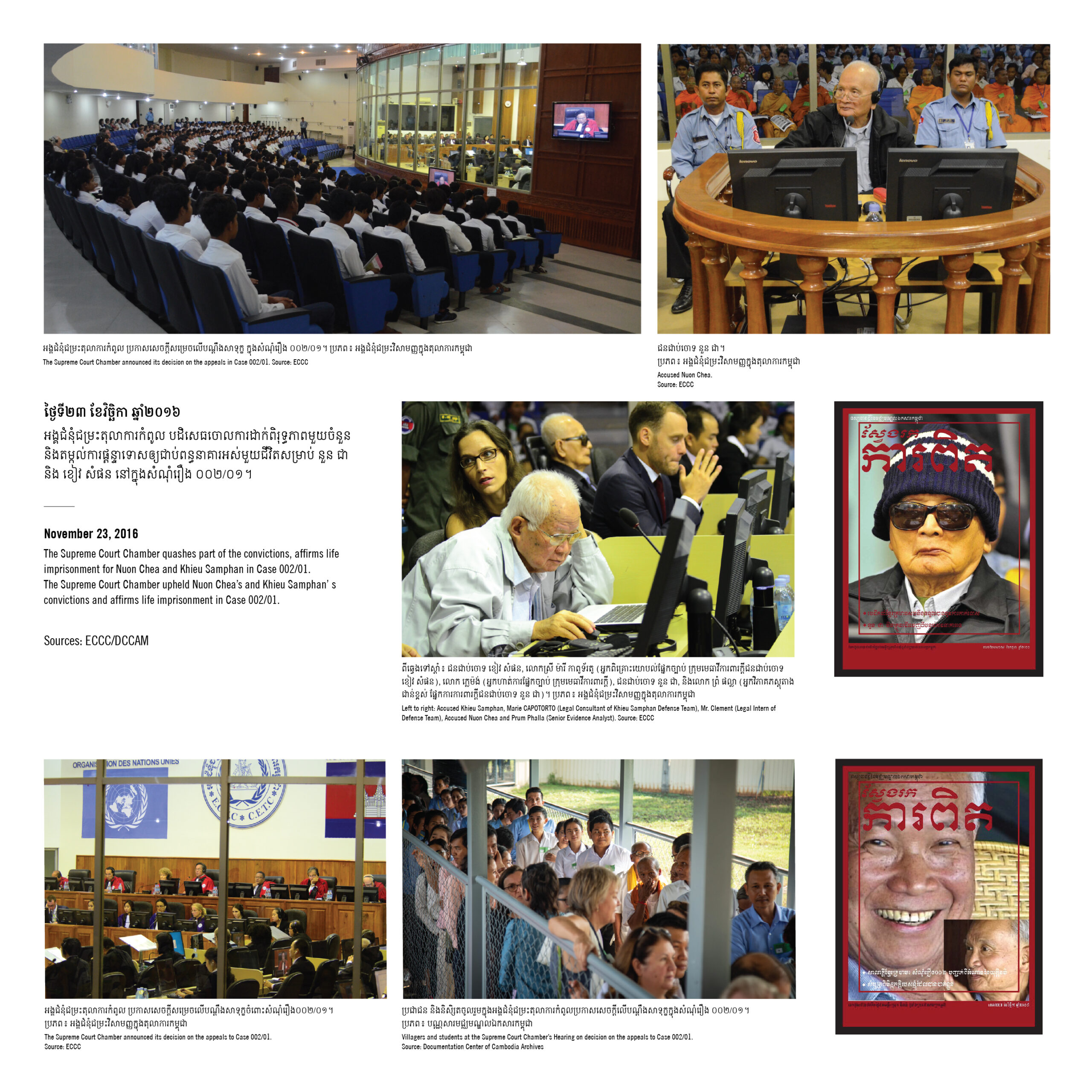

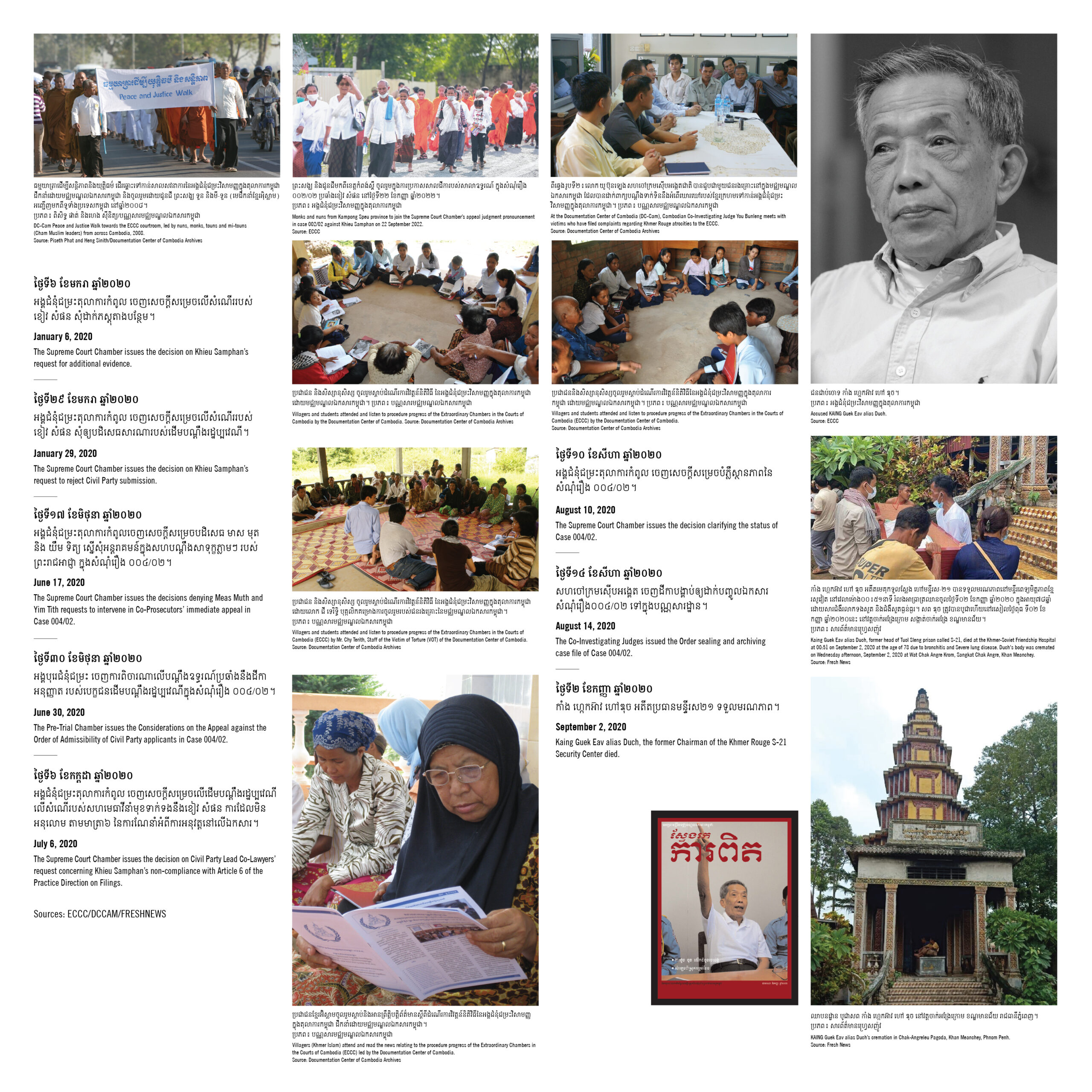

The ECCC’s second case focused on an array of crimes orchestrated around the country by senior Khmer Rouge leaders. The first trial in that case was a complex affair, including multiple charged persons, an expansive investigation, and the involvement of thousands of “civil parties”—survivors represented beside the prosecution as part of the ECCC’s groundbreaking scheme for victim participation. Two of the four charged persons did not face judgment. Former Khmer rouge minister of social affairs Ieng Thirith was found unfit to stand trial due to dementia, and her husband, former Khmer Rouge foreign minister Ieng Sary, passed away during the lengthy trial. The two remaining defendants, senior Khmer Rouge figures Nuon Chea and Khieu Samphan, were convicted of crimes against humanity in 2014. In a second trial, both men were found guilty of genocide, war crimes, and crimes against humanity by the trial chamber, though only Khieu Samphan survived to see his convictions upheld on appeal.

For survivors, the ECCC proceedings brought mixed reactions. Many appreciated and benefitted from the opportunity to join as civil parties and otherwise to participate by sharing their stories. Many also witnessed portions of the process directly in the ECCC’s large gallery, and others engaged in the process through regular outreach events organized by the tribunal and its NGO partners. Many welcomed the taste of justice when the court pronounced its verdicts and appreciated the collective and moral reparations it awarded in collaboration with civil society organizations. However, the length, complexity, and limited legal focus of the proceedings also left some survivors disappointed. Many survivors passed away before seeing any senior Khmer Rouge officials brought to justice. Others lamented the small number of persons charged and wished for a process that would focus more on the crimes they experienced and witnessed every day. Some saw the tribunal as a political affair. Even those most supportive of the ECCC process saw it as just one aspect of a broader quest.

This exhibition includes 16 panels, each representing one year of the ECCC proceedings. The panels highlight key successes and shortcomings of the process. They chronicle the tribunal’s unprecedented judicial investigations into crimes of Democratic Kampuchea, its indictments of senior Khmer Rouge figures, its contentious trials, and its watershed verdicts. The exhibition also shows the ECCC’s limits, such as its narrow jurisdiction and the constraints on its innovative scheme for victim participation. The panels convey the tribunal’s tribulations as well, including legal controversies, administrative challenges, and politicized feuds over further prosecutions. Overall, it shows the ECCC process to be a crucial step in genocide justice for Cambodian survivors but a limited, imperfect one. This chronology of the ECCC’s experience thus points toward the continued need to invest in historical memory and justice in Cambodia.