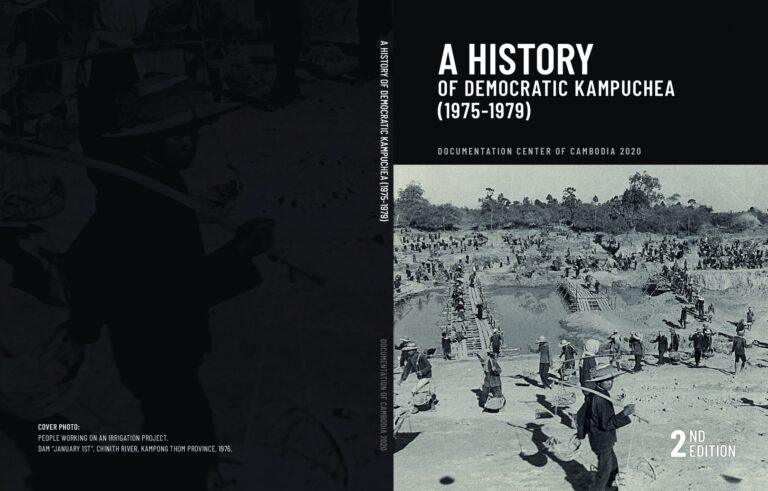

The Documentation Center of Cambodia (DC-Cam) is proud to announce the publication of the second edition of its history textbook, The History of Democratic Kampuchea. The second edition includes new chapters that discuss post-genocide justice as well as new information and stories that have come out in proceedings and decisions of the Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia (ECCC). The second edition provides readers with not only historical information about the Khmer Rouge regime, but also basic facts and concepts about the establishment, organization, and work of the ECCC.

As the authors (Pheng Pong-Rasy, Sopheak Pheana and Christopher Dearing) state in their book, “[t]he ECCC’s judgments helped the Cambodian people and the world come to a better understanding of what led up to and ultimately occurred during the Khmer Rouge regime.” With this book, it is hoped that some of this information can now be incorporated into new classes and lessons for Cambodian students and the public.

None of this would be possible without the incredible support of a number of important stakeholders. DC-Cam would like to thank the Cambodian Government for initiating and supporting the teaching of the Cambodian Genocide since the early 1980s. The Government’s continued support for the education of the younger generation has been crucial to the country’s future.

I would also like to thank the Ministry of Education, who has been a long-time partner with DC-Cam. I hope this book will help countless teachers and students study the country’s dark past.

Thank you to the donors, both those who specifically funded the publication of this book as well as those who provide general support to DC-Cam. Funding for this book was generously provided by Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) GmbH, the Civil Peace Service, the Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development (BMZ), and the Swedish International Development Agency (Sida). DC-Cam would also like to thank the United States Agency for International Development (USAID), which continues to provide generous support to DC-Cam’s work.

Last, but not least, DC-Cam would like to thank the five million Khmer Rouge survivors. Their ongoing effort to re-tell their stories ensures this history will not be forgotten. This book is dedicated to them.

The history of the Khmer Rouge must belong to each and every person in Cambodia, not only as a matter of right, but also obligation. A vibrant democracy depends on the equal rights of all citizens to fully participate in its affairs; however, citizens bear an equal responsibility to be informed stakeholders. A citizenry that is ignorant, dismissive, or unappreciative of its past only invites the hardships and inhumanity that plagued the generations before. Cambodia’s future depends on education, both as a civil right as well as an individual moral obligation. This book will give students and the public one more tool to realize these benchmarks of individual and collective maturity.

Youk Chhang

Director

Documentation Center of Cambodia

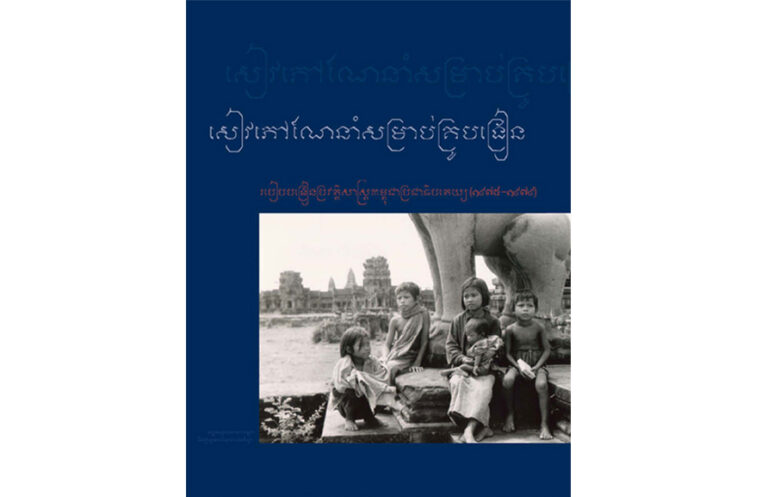

A HISTORY OF DEMOCRATIC KAMPUCHEA (1975-1979)

Download First Edition

Download Second Edition

Translation Disclaimer: The Documentation Center of Cambodia does not warrant the accuracy of this unofficial translation of “A History of Democratic Kampuchea (1975-1979),” by Khamboly Dy. While every effort has been made to ensure its consistency with the original, portions may be incorrect. Any person or entity who relies on or cites to information in this translation does so at his or her own risk. Only the English and Khmer versions of this book may be cited as authentic originals. The translation supported by a grant from Peace building project of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Royal Government of Belgium with the core support provided by the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID).

By Youk Chhang

9 December 2020

(DC-Cam Photo Archives: People working at a work site during the Khmer Rouge, 1975-1979)

(9 December 1948 – 9 December 2020): Seventy-two years ago, on 9 December, the General Assembly of the United Nations adopted the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide (commonly known as the Genocide Convention). The Genocide Convention was the first treaty to recognize the crime of genocide, and it also signified the first human rights treaty adopted by the United Nations. Whereas we remember the anniversary of the adoption of the Genocide Convention for what it means for preventing and punishing the crime of genocide, we should also reflect on what it means for human rights, and how much further we have to go to see a world free of genocide.

The Genocide Convention describes how State Parties can punish genocide through legislation that ensures the prosecution of individuals found guilty of the crime. The Genocide Convention, however, is silent on the particular means by which State Parties can prevent genocide. For many reasons, the obligation to prevent genocide can be challenging to define and enforce, but it is not impossible, and this difficulty should not hinder us in taking some of the most obviously available steps that clearly prevent genocide.

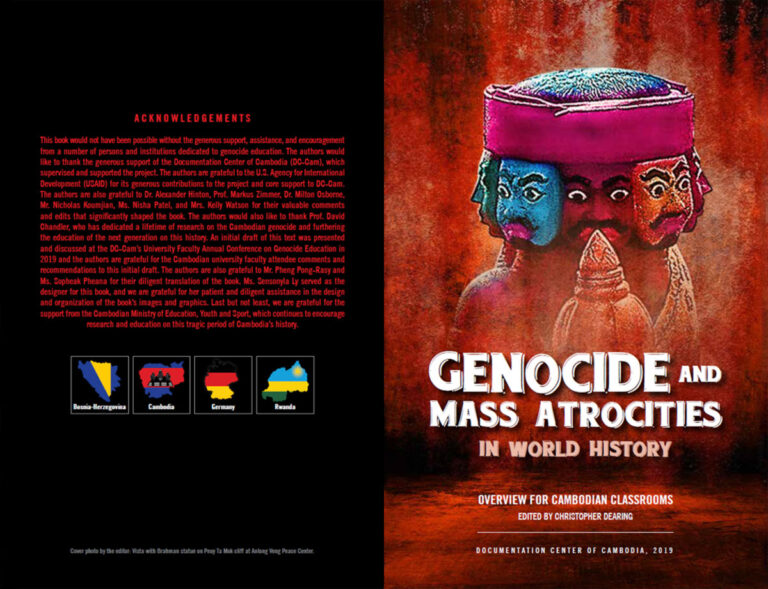

The Documentation Center of Cambodia (DC-Cam) is committed to the idea that genocide education is genocide prevention. Genocide education is more than simply learning historical facts about a genocide; it involves exploring the human experience surrounding the genocide. What experiences, beliefs, or ideas allowed people to justify committing violence on others, and how do these individual stories coincide with community, national, and international circumstances and narratives that may have incited, aggravated, or perpetuated genocide?

DC-Cam also sees genocide education and human rights education as one and the same. The intent to kill or harm a group of people is always preceded by some justification for violence, and the justification for violence is always preceded by many other acts that are based on a dehumanization of people. By objectively studying this dehumanization process, genocide education becomes a direct study of humanity and inhumanity, and, indirectly, a study on how important human rights is in the prevention of the most heinous crimes.

Individual stories play a crucial role in preventing genocide and supporting human rights because they provide an opportunity for people to personally identify with the circumstances of victims. There is perhaps no greater immediate educational output or result in genocide or human rights education than the development of empathy. Empathy thwarts the dehumanization of people through personal reflection of shared humanity. When a young student objectively puts themselves in the mindset and experience of other persons, then he or she has the opportunity to take with them a new understanding of (or at least a new perspective on) how genocide or human rights violations occur, why, and its tragic consequences.

The tragic consequences of genocide transcend time, and the effects can cut across multiple generations even decades later. In writing this essay, I am reminded of the story of Sek Say. For over 40 years, Sek Say searched for the facts surrounding the death of her parents and her little brother at the hands of the Khmer Rouge regime, which oversaw the deaths of over 2 million Cambodians between 1975 and 1979. Her mother, Chan Kim Srun, and her father, Sek Sat, were arrested in 1978 by the Khmer Rouge, but the exact circumstances of their arrest and presumed death were not known to Sek Say. The DC-Cam was able to research and provide to her the records associated with her family. The photograph shows Chan Kim Srun, who was imprisoned in the notorious S-21 prison. Chan Kim Srun was arrested on 14 May 1978, and Sek Sat was arrested shortly thereafter. Sek Say was 11-years old at the time her mother and father were taken from her. In the picture, Chan Kim Srun is holding Sek Say’s little brother, who was five-months old at the time he was killed with his mother. This image is haunting not only because it shows the Khmer Rouge regime’s brutality, but also the emotional pain, trauma, sadness and physical torture that were inflicted on victims before they were executed.

The anniversary of the adoption of the Genocide Convention should not be celebrated because the list of the world’s failures to live up to its duties under the Convention far exceed the few examples of success or progress. We should rather use the anniversary as an important occasion to critically reflect on how much we can improve our efforts to live up to our commitment to humanity. Our commitment to humanity in the Genocide Convention should not begin with measuring our success or failure in punishing the crime of genocide; it should begin with measuring our efforts in preventing genocide from ever occurring. Preventing genocide is not simply a political position; it is a legal duty. The spirit of human rights lives within this duty, and this spirit can be fulfilled through education. Looking across world history and even contemporary events, we should mark this day as a reminder of how much further we have to go.

———————-

Youk Chhang is Director of Documentation Center of Cambodia (DC-Cam). DC-Cam has received numerous accolades and awards for its work in support of memory and justice for victims of the Cambodian genocide. (email: dccam@online.com.kh)