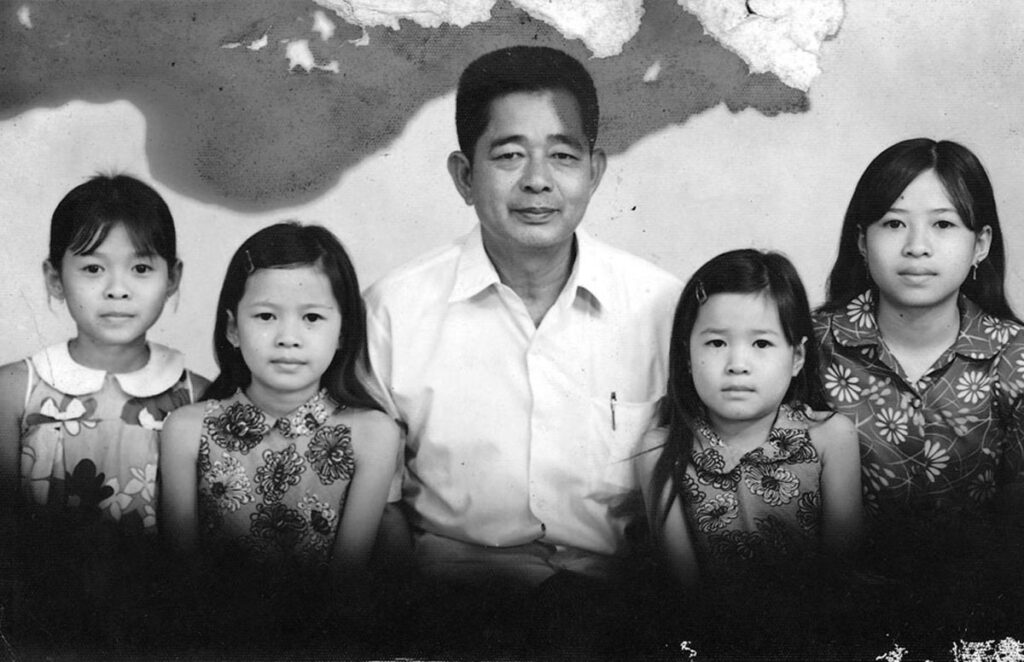

When we were small, my father liked to play with us, pretending he was an elephant. He would take a big mattress, fold it in half, and put it over his head. Then he would extend his arms, sway, and come after us. He would chase anyone in the house.

He inspected schools for a living; it didn’t matter which kind they were, private, Chinese or French. He used to be a school teacher before that. Once I remember that he went to Hawaii and brought back trousers for all of us; they had stripes and were very colorful.

All of us went to French schools where we had two teachers in a class; one was Khmer and one was French. All of my brothers left Cambodia before 1970 and they spoke French fluently. My father would write letters to them in French. He also knew English, Vietnamese, Mandarin and Cantonese. When I went to the market, he could speak to the sellers there in Chinese or Vietnamese.

On the day Pol Pot came to Phnom Penh, my parents had flown to Sihanoukville where they had bought a plot of land. He wanted to live by the beach when he got old. My father loved land; he bought it in Kep, Srey Ambil, and Sihanoukville. He also loved growing things – flowers, plants, and fruit trees. It was his hobby, and mine too. That’s why my mom says I take after him.

My mom’s uncle lived in Sihanoukville. He was a Lon Nol commander, and asked his chauffer to bring my parents to the port and put them on a boat for Thailand. My father wanted to go, but my mom said no because all of their children were still in Phnom Penh. My mom’s uncle left; he’s living in France today.

The Khmer Rouge said “Please, please, go out immediately,” and then shot their guns in the air. So my brother, sisters and I packed very fast, bringing only enough things for a few days, like rice, a pot, and dishes. We left home on April 18. My sister packed my mother’s jewelry in a suitcase with our other valuables and put it in a hole above our rooms. When we came back after the regime, only the hole was left.

My sister’s husband Sophy decided that we should go to his hometown in Prey Veng Province. Eleven of us walked out together. But four of us left Prey Veng a few days after we arrived because we wanted to find our parents; we also didn’t know how to live in Prey Veng. It was very empty there, only rice fields, no fruit trees.

My brother Thorany led us out; it took almost two months to reach my mother’s village by walking on the back roads. The Khmer Rouge kept catching us and forcing us to work, but we kept escaping. When we arrived, the first thing I saw was my father carrying a hoe. Before, he had a big belly, but now, he was very, very skinny. He began crying when he saw us, and said “I waited for you here every day. I prayed for you and waited for you.” Pretty soon, all of us were crying.

He lived for two more years, caring for buffaloes, carrying soil in baskets, and other things. He carried soil at the pagoda, where they told him there was no way he could return to Phnom Penh and have a position as an educated person any more. “You are to work now,” they said.

In 1976, my brother, sisters and I were put in mobile units. At first they let us come home at night, but later they sent us farther and farther away. I learned to make palm leaf hats while I was in the mobile unit; each one took four to five hours, but I could only make them at night, so I needed five or six nights for each. I made them to exchange for crabs or other food when I could. When I knew I would be allowed to go home, I made as many hats as I could and exchanged them for tobacco for my father. He preferred tobacco over food.

We weren’t there when they took him away. Our neighbor said he was caught and they brought him to the pagoda. The Khmer Rouge accused him of wanting to escape from the village and go to see two of my brothers who were living abroad. And they also said no one should follow my father or do the same things he did.

They took my father to Touk Meas prison. On the way, the Khmer Rouge beat him with hard sugar cane, not the soft one we eat. It was very big and hard. After Pol Pot time, I saw a book by the Ministry of Education; they wrote about my father and said they sent him from Touk Meas to Laang Kampot and killed him there.

My mother stayed home from work for ten days after that. She said to the Angkar, “If you want to, please, here are my four children and me. You can kill all of us.” She was very disappointed. They took away nearly all of the people who came from Phnom Penh after that. I waited for my mom’s name to be called, but that time never came.

One of my aunts lived downstairs in the same house as us. She was the women’s leader in the village. She was very cruel and I hated her. She always told her children to watch us: what we did, what we ate, everything. Sometimes my uncle would ask her to please give us food if she had any extra, but she would pretend not to hear. She would even keep it until it spoiled rather than give it to us.

She knew that my grandmother kept a big water bowl made from silver. She reported her to the Angkar, saying she was not honest. Then the cadres went to her house and took everything. After Pol Pot time, there was nothing to eat, not even for my aunt. If she had let my grandmother keep the bowl, she would have sold it and given my aunt food. My grandmother always looked out for her family.

The day my father was taken to prison, she said it should be that way because he deserved it. After the regime, I went to my mother’s homeland and saw her. She said, “Oh, you were very good, and you talked soft,” as if nothing had happened. She forgot what she did in Pol Pot time.

Sometimes when I think about my aunt and some of the others in our village, I’m very angry. But I don’t want to take revenge because now we live in peace. And all of the people in my grandparents’ village are still poor. They took everything from us during the Pol Pot time, but they are still poor. Nothing to do, no education, still poor.